In which we trek into the mind of my youngest and once again get sidetracked.

Over the past few weeks, Mr. T and I have been listening to the first volume of The Story of the World, narrated by Jim Weiss. T has requested that we not only listen in the kitchen, but that we bring the CDs out to the car as well, which is his own rave review. (I must sidetrack a bit myself here and share a small reservation. It seems, although we are only part of the way through the first volume, that there is a bit of bias in the history-telling. I’ve noticed that when Bible stories are conveyed in this book, they are presented as fact; while stories from other cultures are presented as, well, stories. The difference is quite subtle but it’s there. Notwithstanding my own beliefs–we happen to be Catholic–this sort of bias bothers me. We’re enjoying the CDs enough that we’ll continue to listen–but I’ve asked T to listen carefully for further evidence of this bias. Which is an interesting learning experience in its own right.)

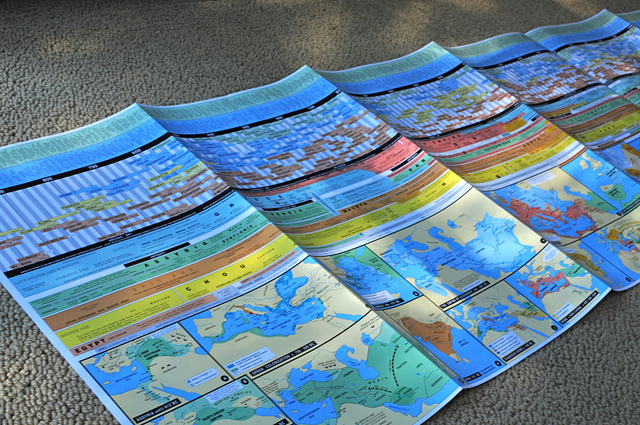

Anyway, as we listened I pulled out this most awesome timeline/history chart that I picked up at our local homeschooling conference last year.

(But wait! I must sidetrack us once again. Gee, I wonder where my kid gets it? When I went looking for an online link to the timeline, I found that the publishers have developed a jaw-dropping online version called HyperHistory. Go see it! Click around on the different sections of the chart, and the different times to see what a rich resource it is. The online version is particularly cool because everything is so darned clickable; I’m linking it in the sidebar too, so no one will miss it. But I like the physical version as well because seeing everything at once gives a different, more global perspective.)

Back to the story at hand: T was quite taken with the timeline. It’s complex and layered; really, it’s designed for older kids and adults. But we looked at it together and deciphered. He loved the little symbols used with some of the historical figures and chronologies. Suddenly he sprang up.

“I want to make a timeline!”

“Of the places we’re learning about on the CDs?”

“Yes!”

At this point I felt like Ultra Homeschooling Mom. I’ve always wished my kids would become interested in timelines, and here T was doing it! I’ve heard of those families who construct elaborate timelines that snake up their stairwells, adding to them over the years and across their studies. I don’t think my husband would exactly go for that, but I’ve often played with notions of making long, pull-out timelines which would live in binders, which we’d layer and adorn over time, putting all of our history studies into conversation with one another.

But here’s the thing: I’ve always had the niggling feeling that such a timeline would be my deal. That the kids would bore of it after the third time I chirped Oh, let’s add this to the timeline! I’ve considered the idea that I could make a timeline and do all of the adding to it, allowing my kids to have an interlaced record of their studies. But somehow I’ve never gotten around to it. It always sounded a bit, um, boring.

Which is why I shouldn’t have been surprised when, after studying the splayed history chart for several minutes, Mr. T looked at me with big eyes and said,

“I know what I can do! I can make a timeline of my own world!”

A timeline of his own world. The world from a grand story he’s writing. Ultra Homeschooling Mom dissolved as quickly as she’d arrived. I mean, that sounded fun and all, but the historical education aspect of his original plans flew out the window. I kept my sigh almost inaudible and talked to T about his plan. If I’ve learned nothing else as a homeschooling parent, I’ve at least learned this: it’s best to take the direction that captures the kid’s imagination. Real learning happens when they’re captivated.

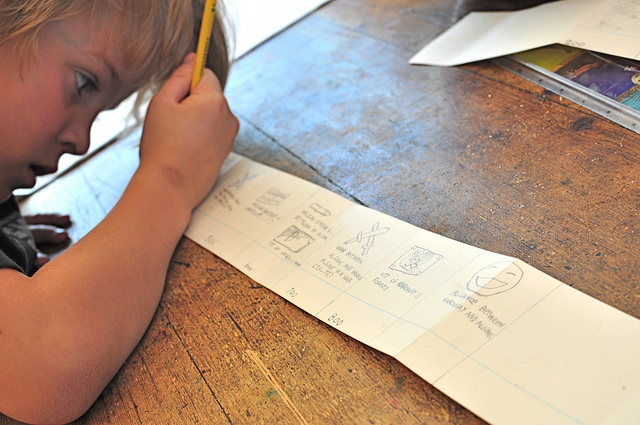

We’d already laid some old sentence strips I’d found in H’s closet across the kitchen table for T’s original timeline. He began to consider what to write first.

“How do I start?” he asked. “Do I start with how the world was created?”

“Why don’t you look the other timeline to see how they started it?”

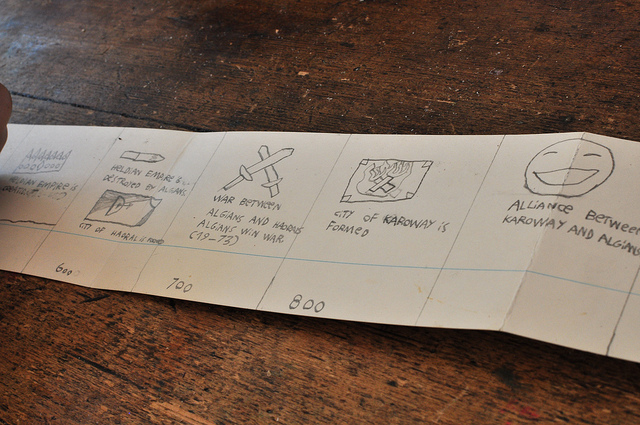

After initially starting with individual creatures and their evolutions, T decided that his history was plodding along too slowly. He went back to the timeline in the living room and consulted. He erased and wrote War between the Gnomashins and Afradys. Afradys win war. (year 39-57)

“I’m making a key!” he sang, drawing a set of crossed swords above his first entry, and in a key at the end of the timeline.

As I watched T run back and forth between the timeline in the living room and his own timeline, I began to see that I might have been wrong about this activity not being educational. T wasn’t simply copying an existing timeline–which is surely what he would have essentially done if he’d made a timeline based on actual events. Rather, he was using a professional model to inform his own notions. After wars, he created cities; after cities he made empires, then more wars, then alliances. The Karoway-Algian Alliance, to be precise. I realized that T was applying not only what he’d learned from the larger timeline, but also what he’d picked up from listening to The Story of the World.

And the best part? T was utterly focused the entire time he worked. As he was the next day, when he pulled out his timeline and added to it as he ate breakfast.

This made me think of the Daniel Pink book A Whole New Mind which I’ve raved about before, and will probably not stop raving about. I won’t attempt to summarize the book, since I’ve already done that, but I’ll remind you of how Pink points out that we parents grew up during the Information Age, when knowing information was a most important life skill. But in this new age, which Pink calls the Conceptual Age, information is accessible to everyone. It’s a mere Google search away. What people need in this new age is an ability to take existing information and apply it. To make it interesting and meaningful to others. To use information as computers and cheap overseas labor cannot. If you still haven’t read the book and you are a parent, go request it from your library. Right now.

T’s timeline was a Conceptual Age timeline. T wasn’t learning to copy existing information; he was learning how to shape the tool of a timeline to his own needs. To tell his own story. This, I understand now, is valuable stuff.

A few days later, Mr. T and I were looking at a book with project ideas for learning about Egypt. He was all fired up about making a plaster map of the Nile. That is, until about thirty seconds later, when his eyes lit up and I knew what was coming.

“Or…I could make a map of my own world!”

Love it!

Me too. 😉

I can just hear his enthusiastic voice. He’s really on to something big this time and with a determined grip, he’s writing it all himself. Thanks for the link to the history resource.

I know–that grip! I don’t think he’s ever going to give it up. His art gets more and more detailed, but the grip never changes.

Thanks, Kristin!

Two somewhat interconnected thoughts:

1. I’ve been thinking a lot about Pink’s idea of Story, and of course that’s how we remember things – content within context. Approaching a timeline as a kind of story, rather than a place to hang disconnected content is so appealing to me.

2. When we were living in our little hut in Thailand (you saw the pics on the kids’ blog), we had a Literature Timeline. This was an 8-foot piece of bamboo (harvested by the kids), on which we marked centuries and half-centuries, an in later centuries, decades. Then we make hanging tags for many of the books we had read a liked, and hung them on the timeline. We continued to do this for all the books we read over the 8 months we were in Thailand. The Literature Timeline was like a meta-story that allowed us to make book-to-book connections and to tie the books we read with real events that had taken place at the same time as the narratives.

I’m in a teaching credential program now, and I know that when I have my own class, I’ll definitely have a literature timeline in there.

Isn’t Pink’s work fantastic? I think you’re right about approaching a timeline as a kind of story: that was something that T did on his own. He noticed that what happened in history–via what he heard on the CD and what he saw on the larger timeline–built on what came before. First there were cities, then there were other cities, then there were wars and then empires… I hadn’t discussed that with him at all, but he picked up on it. Which all goes back to the notion that it isn’t the memorization of specific dates that really matters–although we were required to do a lot of pointless memorizing when I was in school–it’s really the overall view and the connections and patterns that matter. Because history so often repeats itself.

I love the idea of a literature timeline! Did you take a photo of your bamboo timeline? I’d love to see it.