Boy howdy, here we go again–try not to jump out of your skin! It’s time for yet another entry in my year of excellent essayists project.

random notes:

In August I read Pico Iyer, who is widely known as a travel writer, although he writes on a variety of topics, and often on globalism. He calls himself a “mongrel”: his parents were from India, he was born in England, raised in California and educated in English boarding schools, and now lives mostly in suburban Japan, but spends much of his time traveling the world.

Iyer’s work is interesting. His style is less personal, more journalistic than most of the other essayists I’ve read so far. He’s there in the essays, appearing in a paragraph here, a paragraph there, but he’s more like an extra sipping tea to the right of the screen than he is a leading man.

But as he sits off to the side drinking that tea, he’s also, presumably, scribbling in a notebook. Iyer is a master at noting details, so many details. He observes people and places like the outsider he often is–with care, with curiosity. Then he analyzes those details for the meaning that connects them. There’s plenty of insight in an Iyer essay.

There’s also that lyricism that I always admire in writing–a rhythm to the lines, an attention to the sounds. There are single sentences that gallop on for a paragraph, and analogies that make me smile for the ride.

Perhaps because so many of his essays reflect on varied cultures, there’s a focus on disparity in Iyer’s work. Disparity between the rich and the poor in Haiti; between the jet-lagged and the un-jet-lagged mind; between the English language of England and the English of India. That theme of disparity continues even in essays not focused on travel: an essay on Leonard Cohen, for example, studies the disparity between the Cohen of legend, and the Cohen who resides in a Zen center as “cook, chauffeur and sometimes drinking buddy” to a Japanese roshi.

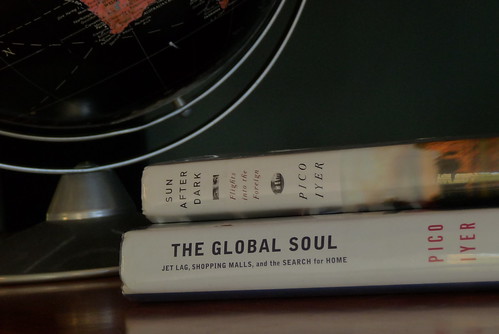

I focused my reading on two works: The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls and the Search for Home, and Sun After Dark: Flights into the Foreign. The subject matter in these essays is fascinating enough–the L.A. airport, the Olympic Village in Atlanta, shopping mall-hotels in Hong Kong from which people never leave, Angkor Wat, the Dalai Lama–but then there’s Iyer’s analysis, and his talent for crafting fine lines. It’s intriguing stuff. See for yourself.

a few lines to love:

“And suddenly, in a flash, I am taken back to myself at the age of nine, going back and forth (three times a year) between my parents’ home in California and my boarding school in England and realizing that, as a member of neither culture, I could choose between selves at will, wowing my Californian friends with the passages of Greek and Latin I’d already learned in England, and telling my breathless housemates in Oxford how close I lived to the Grateful Dead. The tradition denoted by my face was something I could erase (mostly) with my voice, or pick up whenever the conversation turned to the Maharishi or patchouli oil”

Such great details.

“I woke up one morning last month in sleepy, never-never Laos (where the center of the capital is unpaved red dirt and a fountain without water), and went to a movie that same evening in the Westside Pavilion in Los Angeles, where a Korean at a croissanterie made an iced cappuccino for a young Japanese boy surrounded by the East Wind snack bar and Panda Express, Fajita Flats and the Hana Grill; two weeks later I woke up in placid, acupuncture-loving Santa Barbara, and went to sleep that night in the broken heart of Manila, where children were piled up like rags on the pedestrian overpasses and girls scarcely in their teens combed, combed their long hair before lying down to sleep under sheets of cellophane on the central dividers of city streets.”

That’s a single sentence. Which is a brilliant construction, given that he’s writing about dragging oneself across the globe and how “such quick transitions bring conflicts”. Iyer drags us along on his long-winded sentence, and as we try to make sense, we feel his disorientation ourselves. Read the very last part of the sentence aloud, and listen to all the “s” sounds. Lovely.

“In the final winter of the old millennium, to see what the official caretakers of our global order make of all this, I accepted an invitation to go as a Fellow to the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. The Forum gathers hundreds of “leaders of global security” in Davos each year–captains of industry, heads of state, computer billionaires, and a few token mortals such as me–to map out the future of the planet.

I had to include this as an example of the essayist’s “self-deprecatory cough” that Adam Gopnik writes about. A few token mortals such as me seems suitably self-deflecting.

The following is from a section of an essay called “The Empire”. Iyer writes about sitting at Cambridge with a friend, a fellow Indian, who has embraced England as his home and his lifestyle, but suddenly expresses disillusionment with his decision.

“I look at him and don’t know what to think. The punts are drifting past the shortbread-colored towers, and the late-summer light is gilding the fields and distant spires as in the kind of watercolors the Empire sent around the globe. My friend has a big heart, I know, and a quick mind, but both are so lost inside the character he’s chose to play that all I can hear, sometimes, is the sound of a lover disappointed, a boy who’s left everything he knows to pursue some ideal, unattainable woman, and arrives at her doorstep, only to find she’s given herself over to some mobster from Las Vegas.”

Ah. The “shortbread-colored towers”. The watercolored light. And then the mobster from Las Vegas at the end. Beautiful writing. (And doesn’t it remind you a little of E.B. White’s Corn Belt boy with “a manuscript in his suitcase and a pain in his heart”?)

On how travel can haunt us:

“When we sleep, as we do for perhaps a third of our days, we see not the places we know so well so much as somewhere we might have visited once, magically rearranged. Even when we’re lying sleepless in our beds, trying to will ourselves into the dark, what we meet, often, are not the people who surround us every day, but a stranger, perhaps, whose eyes met ours in a cafe in Reykjavik twenty years ago.”

I just like the idea he presents here. And that Reykjavik stranger.

From that essay on Leonard Cohen and his relationship with the roshi:

“It’s touching in a way: the man who has been the poet laureate of those in flight, who has never found in his sixty-three years a woman he can marry or a home he won’t desert, the connoisseur of betrayal and self-tormenting soul who claimed, twenty-five years ago, that he had ‘torn everyone who reached out for me,’ and who ended his most recent collection of writings with a prayer for ‘the precious ones I overthrew for an education in the world’– the man, in fact, who became an international heartthrob while singing “So Long” and “Goodbye” — has finally found something he hasn’t abandoned and a love that won’t let him down.”

Another one of those long Iyer sentences. I love how he carries us along.

On considering Singapore while jet-lagged:

“Along the shiny malls of Orchard Road–the new, official Singapore, where Barnes & Noble and Marks & Spencer and Nokia and Nike all share a single entrance (there’s a Starbucks on this intersection, a Starbucks on that one)–tall girls who weren’t girls when the day or the decade began flounce outside the Royal Thai Embassy, walking up the sidewalk, walking down it.”

These lines are all about the sounds for me: the rhythm in the rattling off of the “and” shops; the repeat of the words Starbucks and girls; the alliteration in day and decade. And then the walking up and walking down. It’s almost singsong–a perfect way to convey the altered jet-lagged mind.

And more on jet lag:

“I feel, when lagged, as if I’m seeing the whole world through tears, or squinting; everything gets through to me, but with the wrong weight or meaning. I can’t see the signs, only their reflections in the puddles. I can’t follow directions; only savor the fact of being lost. It’s like watching a foreign movie without subtitles, perhaps: I can’t follow the story, the arc of character, but something else–the inflection of a hand, this unregarded silence–comes through to me intensely.”

Yes! This describes the state of jet lag so well. Such apt analogies. And again, the rhythm of the lines.

The essay “A Far-Off Affair” examines the English language in India. This particular essay has a more humorous tone than most of Iyer’s work; as a fellow wordlover, I ate it up.

“Indian English, when it is not overly formal, comes at you with the fatal tinkle of an advertising man who’s got his hands on the Ten Commandments: there’s always a trace of sententiousness in it, and yet the lofty sentiments are placed inside the jingly singsong of a children’s ditty. A decade before, traveling across my stepmotherland, I’d been struck by the signs that said LANE DRIVING IS SANE DRIVING and NO HURRY, NO WORRY, but now they had been joined by half a hundred others, trilling, RECKLESS DRIVERS KILL AND DIE, LEAVING ALL BEHIND TO CRY (or, a little more potently, RISK-TAKER IS ACCIDENT-MAKER). As I drove out of little settlements crammed with such instructions, the signs offered brightly, THANKS FOR INCONVENIENCE.”

And:

“But I always felt that I was speaking a language quite different from the English being spoken all around me (more Indians, of course, speak English than Englishmen), and came to feel that the one companion who’d been with me all my life, the English language, had stolen away into a corner and come back in a turban, a finger to its lips.”

There were so many funny examples in this essay; it was hard to know which to include. Just as it’s hard to stop reading Iyer. But it’s September and time to move on.

the plan for september:

I meant to read M.F.K. Fisher earlier in the summer–she’s summery reading to me. But here near the San Francisco Bay, the best summer weather is just now in full swing. So Fisher it is.

I really like that last quotation. When I was 21 I lived in Russia for a year. For the last 4 months I spoke almost no English. My English actually got rusty. I couldn’t remember the words for everyday objects. Once at the American embassy my English was so bad that the guard scrutinized my passport thinking it was a fake. I had a profound sense of self-alienation. Different from the one Iyer describes, but the image of the language sneaking off and returning a stranger is wonderful.

And the jet-lagged eye seeing only the reflections of signs in puddles. I have had that feeling of being jetlagged and dazzled by lights and unable to make sense of anything.

Thank you for distilling all these essayists into a few wonderful quotations for us. I feel I have learned something from your project.

You lived in Russia for a year?! Holy smokes, you just get more interesting with every comment!

I feel a little guilty accepting gratitude for distilling these essayists for you. It’s a very selfish project. Posting here keeps me diligent, and makes me put thought into what I write. But I’m doing it because I’m hoping I’ll have learned something by the end of the year. It seems almost ridiculous to think that anyone else would enjoy reading these posts–but if you’re reading and you’ve learned something then, dang, that’s satisfying!