The next post in a series.

Taking dictation is a technique that is often used in classrooms with young kids–say kindergarteners and first graders. It’s also a technique occasionally mentioned in books on writing for homeschoolers. However, dictation often seems to be treated as a temporary fix, as something you do for a short while, until children can string a few words together on their own.

I’d like to argue that taking dictation can be a helpful technique for far longer than that. It can be used with kids who are beginning to write on their own, and even for those who are fluent writers. (At some point this month I’ll post more about how I used dictation to help my teenage son with his writing.) I’d like to share a section from my book draft that shows why I believe this is so:

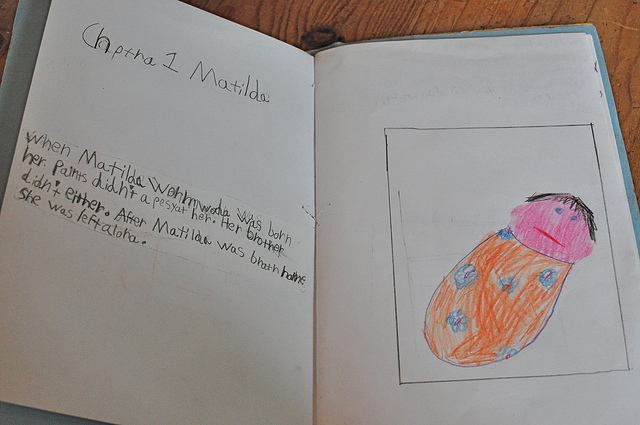

One Friday morning when Lulu was seven, she approached me as I washed dishes with one of those singular wide smiles that tell you the kid has been up to something. She pulled an object from behind her back and handed it to me, wordlessly. I dried my hands and took into them a book I had never seen before—a book crafted in cardboard, glue stick and red construction paper and titled in careful cursive, Matilda.

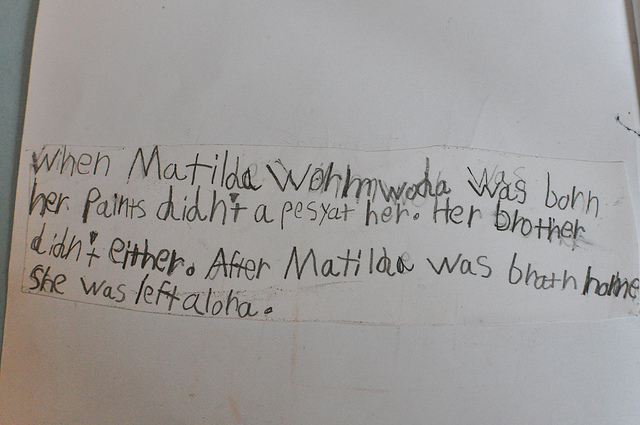

I opened it and began reading: When Matilda Wormwoda was born her paints didn’t a pesyat her. Right off, I was charmed by Lulu’s spelling of appreciate and the tiny inverted triangle that stood in for the apostrophe in didn’t. The book turned out to be a retelling of Roald Dahl’s tale, based on Lulu’s many listenings to the audiobook and made secretly, over the course of a week, in her bedroom. Her book continued, scene by scene, right up to the last in which Matilda jampt into Miss Hany’s arms and hag her. Lulu had managed to retell the entire novel in 23 pages, in fanciful spelling and colored-pencil illustration, all by herself.

It was quite a feat. If Lulu had been my first child, I might have taken her book as a sign that it was time to push her out of the nest and make her write on her own. But I had the sense to realize that just because she could write on her own did not mean that she always wanted to. I hadn’t stopped reading to her simply because she was beginning to read on her own; likewise I continued taking dictation from her when she requested it. A few months later, Lulu had a new story, which she dictated this time, based on her own character, a chipmunk named Chester.

It’s interesting to compare lines from the two stories.

Matilda is filled with short, simple lines that follow a similar pattern (I’ve translated Lulu’s words to conventional spelling here to help you to focus on the content):

“It was about a ten minute walk to the library. Matilda went into the library. She went up to the desk. At the desk was a pretty woman. Her name was Miss Phelps. Matilda asked where the children’s books are. After Matilda had read all the children’s books she went to Miss Phelps to ask her what to read next.”

Chester, written just six months later, reads quite differently:

“Chester walked into the living room, lured by the smell of the cake. Chester (being a chipmunk) usually got nuts and fruits from trees, so he thought the smell was coming from the light bulbs on the chandelier, which looked like fruits to him. Unluckily, the chandelier was on!

Chester jumped from the back of the couch to the chandelier. He grabbed on to the middle part of the chandelier that the light bulbs were hooked on to. Chester did not notice that the room was full of people! They did not notice him.

Chester made his way up a metal bar. “Mmm,” he thought to himself, “what shiny fruit!” He grabbed on to a light bulb. Suddenly his paws grew very, very hot and he let go!

He fell down into the bean dip.”

Granted, Chester was written six months after Matilda, but I think the differences between the two stories have more to do with the manner in which they were transcribed. Matilda was written independently, and Lulu’s concentration went to the basic tasks of printing letters and spelling, one careful word after the next. Each simple sentence leads directly to the next, like a plodding hike up a hill, step after labored step. I don’t mean to minimize Lulu’s work; retelling Dahl’s entire story on her own at seven was truly a grand accomplishment. But the triumph of the story isn’t the content: it’s the independence and the scale of the project.

On the other hand, it’s the storytelling of Chester that shines. Since I did the writing, Lulu could direct her energy to the telling of the tale. She uses complex sentences, and parenthetical asides. She neatly inserts internal monologue for Chester, broken up for clarity and rhythm. (“Mmm,” he thought to himself, “what shiny fruit!”) She makes the choice to place the line He fell down into the bean dip in its own paragraph for comic effect. And her lines, bolstered by a seven-year-old’s love of (well-placed) exclamation marks, are vibrant. They have a confident fluidity.

I could see that Lulu was developing her voice as a writer.

* * *

This notion of developing a writer’s voice is vital. It’s a skill that many of us were unable to develop in school because writing was taught as a series of rules, through assigned topics. This only managed to trip us up. Consider this quote from William Zinsser, from his book Writing To Learn:

“What does preoccupy me is the plain declarative sentence. How have we managed to hide it from so much of the population? Far too many Americans are prevented from doing useful work because they never learned to express themselves. Contrary to popular belief, writing isn’t something that only ‘writers’ do; writing is a basic skill for getting through life. Yet most American adults are terrified of the prospect–ask a middle-aged engineer to write a report and you’ll see something close to panic. Writing, however, isn’t a special language that belongs to English teachers and a few other sensitive souls who have a ‘gift for words.’ Writing is thinking on paper. Anyone who thinks clearly should be able to write clearly–about any subject at all.”

Taking dictation helps children get their clear thoughts down on the page. It puts the mechanics of writing aside so the child can work on self-expression. Yes, kids will need to learn those mechanics in time, but that learning can happen quite naturally if we take it slowly, and place self-expression first. And I will bet that kids who learn to write this way will not become middle-aged engineers–or middle-aged people of any persuasion–who are terrified of writing a report.

I have a previous post on Lulu and how her writing voice developed through dictation, if you’re interested.

I love, love, love Lulu’s story about Chester. She obviously has a sense of humour.

I agree with your observation:

“… just because she could write on her own did not mean that she always wanted to. I hadn’t stopped reading to her simply because she was beginning to read on her own”.

Absolutely – so true! That being said, some kids are not interested in dictating once they’ve savoured the independence of writing. As soon as my middle daughter learned that she could write she was off – writing on napkins, in journals, on reams of lined paper. On occasion she will share something that she is especially proud of and I will type it up as a good copy. Mostly though, she plods along kneading her “lumps of clay”.

I’m going through this with T, too. He is just beginning to want to write independently rather than through dictation. I’ll write more about that in an upcoming post…

I did find that my older two sometimes liked to return to dictating when they had something particularly challenging to write. At a certain age they preferred to do their creative writing on their own, but if they had to write for a class, or on a topic that required extra thought, they might ask me to take dictation from them. At least to get them started.

But we should have worse problems than having kids who won’t offer dictation to us, right? This is just how learning should progress: we help them begin, and then they find their own way, in their own time. It’s much better to have them insisting on doing it themselves, rather than having us nagging them to get a few words down on a page.

Hey – Just wanted to share a story. I’m student teaching in a 5th grade classroom. During Writer’s Workshop yesterday, a lot of kids were able to dive in to their writing after listening to a story and being offered some good prompts. One boy was stuck. Stuck stuck stuck. I saw him talking with a classroom volunteer – they made a list of things he could write about. Five minutes later he had “Green Day” written as a title, but the rest of the page was blank and he was still stuck. I grabbed a pencil and said, “Tell me about Green Day.” He started talking, I started writing. Within just a few minutes, he had a page full of wonderful writing with a little personal history and great connections to song lyrics. Better still, he had increased confidence that he was indeed a writer. Today, I took a little dictation from him during writing time, then he got a pencil and continued on his own. Yay!

Awesome, awesome, awesome! This is just what I’m talking about when I say that dictation can help for older, fluent writers. It can be just the thing to get them past being stuck stuck stuck. Yet it’s a technique that people toss aside once kids hit a certain age.

Good for you for recognizing that dictation might help him! And isn’t it wonderful how a single session of dictation changed his perspective of himself as a writer? Today you only needed to do it to get him going, and then he was on his own. Just what we’d hope for.

(And I’m so glad to hear that writer’s workshops are still being used in classrooms–I worry that this age of testing and standardization might phase them out. They were the highlight of the day for many of my students, way back when I taught.)

Thanks so much for taking the time to share this, Jill. It made my day!

P.S. I also think your “tell me about Green Day” was the perfect invitation. “Tell me about…” is a great way to get kids talking. You aren’t asking for a story, or an essay, or any particular type of writing. You’re just getting them going, and helping them realize how much they already have to say.

They can always shape what you get down later, into a particular type of writing. This is often how I get started with my own writing: just scribbling down what I know and watching where it leads me.