If you ever think it might be fun to rile me up, to get me talking so fast that my sentences overlap and my hands dart about like an Italian grandmother’s, just say the words “five-paragraph essay.”

Really. Ask the moms at my homeschool park day what I do when the topic comes up. Ask my wonderful neighbors who kindly fed our family a decadent meal of Dungeness crab last week, only to get paid back with an earful from me. The same earful I’ve clogged their ears with before.

I can’t help myself. Just thinking about the traditional school essay carbonates my blood somehow and makes me want to explode. But I take comfort in knowing that I’m not the only one.

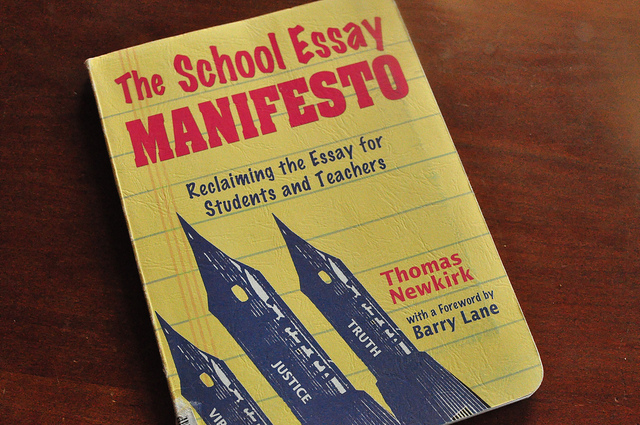

I love this little book. This manifesto. This argument for what a school essay shouldn’t be–and what it should.

My own ire for the five-paragraph essay got stirred up a couple of years ago when H decided to go to high school as a junior after a lifetime of homeschooling, and I argued to have him placed in Honors English. The year before, he’d taken an Advanced Placement English Language and Composition course online, and although the instruction had been via computer, it was fantastic. H had learned to write essays that combined analysis of literature with reflection about his own life. It was a challenging course, and I had to help him a good deal, especially in the beginning, but the work got easier and his writing became clearer and more expressive over the course of the year.

The high school class was different. Very different. Each assigned essay arrived with packets of information explaining how the essay should be written. Essays were defined by how many paragraphs they should include: there were one-paragraph essays, three-paragraph essays, five-paragraph essays. Each paragraph had its own set of instructions: what the first sentence should say, where the thesis should come in and what it should look like, what the lines that came between should say and how the paragraphs should end. Those final sentences irked me the most. The teacher wanted a line which summarized the paragraph before–I can’t think why. Perhaps it was an attempt to insure that students keep paragraphs on-topic, but those final lines had all the finesse of a loosened engine part dragging below a truck on a country road.

“This is bad writing!” I ranted to H. “No writer ends paragraphs with summaries of what came before! You know that, don’t you?”

Of course he knew that. He’d been listening to and reading good writing for most of his life. And perhaps that was the biggest irony: H’s assigned task was to respond to masterful literature, yet he couldn’t use that literature as a model for his response. No, he had to follow his teacher’s line-by-line, paint-by-the-numbers instructions. And those instructions didn’t lead to good writing. Instead they led to predictable, controlled pseudo-writing that didn’t look like anything you see in print in the real world.

But it had one thing going for it: fitting a mold as it did, I imagine it was easy to grade.

From Newkirk’s Manifesto:

“Without the lure of uncertainty and surprise, writing would be drudgery. If beginning writers never have this experience of the writing taking over–the emerging language outpacing the original intention, the digression becoming a central part of the writing–they will never understand what it is that motivates writers. And the essay must be open enough for this movement into the unknown.”

Newkirk nails it here. I can’t tell you how many interviews I’ve read or heard with professional writers who, when asked why they write, respond with something along the lines of to figure something out. Writers write to discover, to pinpoint, to clarify. It’s in the process of so many dead-ends and crumpled papers that a writer refines and even re-discovers the thesis he or she is after. Giving kids a fixed template for their writing denies them this self-discovery. They lose out on the very thing that makes the act of writing compelling: the lure of trying to put into words what you really want to say.

I’m nettled by the fact that these five-paragraph recipes are even called essays. I love the essay form. The word essay comes from Montaigne, the father of the essay, and the second essayist I wrote about in My Year of Excellent Essayists series. As I wrote in that post, “The word essay originated in the term Montaigne used to title his writings: essais, which is French for attempts, or trials. My Oxford English Dictionary says that the early essay was considered unfinished, ‘an irregular, undigested piece’. A musing.” Montaigne wrote to try to pin down his ideas; his essays are rambling pieces that, as Newkirk points out, mimic the way the human mind works.

As I helped H struggle with those assigned essays, I was in the midst of reading masterful essayists for my blog project. Guess what? E.B. White never once ends a paragraph with a line that awkwardly restates what he’s just said. Joan Didion does not start her essays by blatantly stating her thesis in the first paragraph and then proceeding to prove it. Annie Dillard does not cram her thoughts into five paragraphs, Adam Gopnik does not support each of his ideas with three pieces of evidence, and Michael Chabon never ever recaps the main points of his essay in his final paragraph.

English teachers who cling to this formulaic type of instruction would probably argue that they’re trying to prepare their students for the academic writing of college. I would argue back that this sort of instruction teaches kids to write to a formula, but it doesn’t teach them to write. It doesn’t present them with the challenge of trying to figure out what they have to say, and then deciding how to structure their ideas into a form that will move a reader.

In But How Do You Teach Writing?, Barry Lane responds to the academic writing argument this way:

“I understand the importance of what is sometimes referred to as formal academic writing, but I also know that the best academic writing has a voice behind it. Not an informal voice (‘Hi, my name is Bill and I’m going to tell you about protozoa…’) but a creative, inquisitive voice that makes you want to keep flipping the pages. In Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink and The Tipping Point, both of which deal with hard science, Gladwell seduces his readers into his investigation and delights them with the facts he uncovers. Any kid who can write like that in college will rake in the As, and if he or she writes a Ph.D. dissertation, it might get published without major rewriting.”

Sadly, any kid who is restricted to formulaic writing prompts will probably never develop this sort of creative, inquisitive writing voice.

Newkirk writes that these essay formulas are rooted in composition textbooks from the 1950s. I suspect that they’re still around not because they’re particularly effective in teaching students to write–but because formulas are easy to teach and fomulaic writing is easy to grade. Which makes you wonder who they really serve: the student or the teacher?

H ended that year of Honors English with a major term paper. The paper was described as “an expanded version of the five-paragraph essay we’ve been practicing since 9th grade.” (These kids had spent three years learning to write to a single formula!) H chose to research the Native American writer Sherman Alexie. H had a personal connection with Alexie. The year before he’d participated in a film project for teenagers on the Tulalip Indian Reservation outside Seattle. The students arrived on a Thursday, were placed into teams of seven and given 36 hours to film and edit a scene adapted from Alexie’s book The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian. H’s collaboration was a somber, beautifully cinematic piece that captured the sense of loss and hopelessness that can haunt reservation life. On Sunday the films were shown at the Seattle International Film Festival, with Alexie in the audience. Afterwards, H was introduced, and shook Alexie’s hand.

I’d raved to H about how meeting Alexie would make a great introduction to his term paper, especially given that most students were writing about American authors who, like Poe, Dickinson and Fitzgerald, happen to be dead. But no. H showed me how the term paper instructions explained that students could start their papers with an interesting opening line, just one, before they moved into the other specific requirements of their introductory paragraph. The fact that H had met the subject of his term paper was inconsequential. It may have been a formative experience in his life as a young filmmaker, but it didn’t fit the formula. There was, essentially, no room for H in the formula.

As a parent and a writer, this broke my heart a little.

I do realize that all English teachers don’t teach this way. When I taught elementary school I was involved with the Bay Area Writing Project at UC Berkeley, which is part of the larger National Writing Project, an organization that promotes progressive writing instruction in schools. The Project does great work in training teachers in alternative writing methods. There are numerous effective ways to teach writing, and numerous teachers doing just that. But in our current culture of standardization and testing, it can be harder and harder for teachers to find time and support for this sort of alternative writing instruction. And that breaks my heart a little too.

What can homeschoolers do? Ah, there’s enough to say to fill a book–and I’m working at that! But here are a few tips: When considering how your child might learn to write, try to disregard the formulas you may remember from your own writing education. Don’t worry so much that your kid learn to write in a certain formal, factual style. Instead, allow kids to write about their passions. Don’t look to textbooks for models; look instead to the best writing you can find. If your kid is interested in science and the environment, read articles in National Geographic. Kids interested in the arts can study well-written reviews in areas of personal interest: film, dance, music, theater, visual art. Kids interested in gaming can read well-written gaming magazines. And so on. Let them read models that interest them, and let them try writing like that.

Then again, if a kid wants to write only poetry or fantasy novels, that might not be a bad thing either.

I think it matters less that kids have experience writing in particular styles and formats. You may think me a heretic for saying so, but I don’t think it even matters so much that teenagers learn to write formal papers. What matters more is that kids write about what ignites them. That they have experience writing on subjects that draw them in, compelling them to take words and really work with them, grappling and wrestling and pinning them down into what they want to say. What matters is that kids learn to use words to express themselves. That’s how they’ll develop that voice that Lane writes about, and if they get that far, they’ll have it made. They’ll be able to tackle any writing–even formulaic writing–that someone might throw at them later. In high school, for a college application, for college, on the job, in life.

So now Lulu’s chosen to attend that same high school, and is receiving those same English assignments. And I know it’s about time for me to head over to that school and step on my soapbox. Not that it will make any difference, but I can’t sit by just writing blog posts and essays about my frustrations. I have to do what I can to try and force some change.

I won’t end this post by recapping what I’ve already said; instead I’ll share some good news. In H’s first semester at NYU, he’s taking a required freshman course called Writing the Essay. Right there on the syllabus it tells students, essentially, to forget everything they may have learned about the 5-paragraph essay. Instead, students read essays (or watch films!) and look for personal connections. They do a variety of exercises to try to interact with the material in different ways. They discover which approaches help them express their ideas best, and then they begin to write their essays.

That’s enough to get me off my soap box. And enough to make this writing mama’s heart sing.

Brava!

More than sometimes I suspect that I am a little trashed from “learning” to write in high school. I excelled at things like the 5 p essay and “bing bang bongo” because they are as easy to do as they are to grade. And now, 20 years later, I feel like those practiced gears stick in the way of expressing myself as I intuitively know I want to…

the irony is not lost on me, as you point out, that we study great literature in many schools and when it comes time to interact with it we are asked to tame our response. Crazy, when couched that way.

I guess the antidote is to write, and write, and write. Sometimes erasing memory and habit is the hardest work!

Thank you, this post made me smile and feel so validated.

I agree with you, Amy–I think that “learning” to write via formula can trash kids’ natural written expression. H has always been a strong, avid writer, but that one year of intense formulaic writing instruction really messed him up. It convinced him that he didn’t know how to write, and that he was a bad writer. A year later, when he began writing his college application essays, I had to do a lot of urging to help him realize that he still had that strong, expressive writer inside him.

And yes, the antidote is to write, write, and write–about what you want to write about, in the way you want to write it!

Thanks for your feedback. You made me smile too.

Wow Patricia — I can see that formula makes you crazy!

I don’t think our approach is as rigid in Canada (at least not in my experience). In fact, the “5 paragraph essay” is new to me. Certainly, for my son (with an LD in writing) breaking an essay down into parts and simplifying the process works.

I can’t explain how we were taught (ahem, 30 years ago) without drawing a diagram. But our teacher in grade nine used to tell us that the paragraphs should be “hooked” like boxcars on a train — that the ideas should lead naturally into the next by a progression of thought. I used to like that idea of the train — the ideas moving and joined with flexibility.

Crazy, yes!

I’m not against breaking things down and simplifying the process. I’m just against the idea that the process is broken down to such a degree that it dictates what should be in each paragraph, and how those paragraphs should look. That doesn’t allow kids to think.

Ideas progressing naturally from one to the next like boxcars is a helpful image–it isn’t constraining, like formulas can be. I often use a similar image of pearls on a string when helping my kids.

The content should dictate the structure, rather than the structure coming first.

I think we’ve written back and forth about the Post-It outline idea: when my kids are working on essays, I have them put each idea on a separate Post-It or index card. Then they sort the cards and form their own outlines. Their sorting dictates how many paragraphs they’ll include–and they often go back and write their opening and closing paragraphs last, because those are so important.

It’s always fun to chat about writing with you, Peaches!

WOW! Fantastic- this gives me so much to think about. Also, it boosts my confidence straying from the public school curriculum as we begin homeschooling.

Thank you-

I’m glad the post got you thinking, Melissa. Just what I was after!

I think it can be helpful to constantly question the public school curriculum when it comes to writing. Do kids really need to take on all of their own writing at age five and six? (Only in traditional classrooms where the high student to teacher ratio makes writing necessary.) Should they only write stories as young kids, and factual, report-style pieces in upper grades? (Absolutely not, but traditional schools have a need to parse out skills over school years to make sure students are “covering” everything.)

I could go on and on. The truth is that writing can develop quite organically, as learning to speak does. But for that to work, we have to let go of many ingrained preconceptions that we probably picked up in school.

Keep straying!

Hi Tricia,

I’m really glad you put into print what I’ve heard you complain about for some time now. Your passion is evident and catching. I believe what you are writing darling. You’ve convinced me.

It is my hope that you will share your insight with L’s teacher though, who isn’t the only one who needs to be tactfully questioned. Chet was just ridiculed for including style in his science report. I guess science papers are off limits for including sentiment.

It seems like the five paragraph essay is a metaphor for human-nature to create order and routine, so that we (or someone in academia) may feel in control.

Since it makes for more interesting reading, I’d rather gather the reigns and aim for tone, a freaking insightful voice amidst the drone of what’s perceived as normal.

I look forward to an update about your mission.

You are right-on about the five-paragraph essay being a metaphor for control. We don’t want kids thinking! They might go off-topic, and then their work would take longer to respond to and grade!

It burns me up that Chet was ridiculed for including style in a science report. Guess whoever ridiculed him hasn’t read any good science writing lately! Guess he or she didn’t see that quote from Barry Lane above, about how Malcolm Gladwell’s books are successful because he combines hard science with good writing. The ability to write like that is an incredibly valuable life skill! Yet we’d rather encourage kids to write boring reports that no one wants to read because it’s easier to convey our expectations that way; it’s easier to make sure they’re doing what we tell them to do.

One point for the teacher; zero points for the student.

Maybe you could help Chet find some good science writing, and bring it to whomever gave him a bad time. See if the kids in his group could try a different model for their next writing project… In our teen writing workshop last year, we did an exercise in which kids wrote as if they were an inanimate object. One kid wrote in the persona of a cold germ and the writing was hilarious–but it also could have been instructive, if he’d written it after researching the science of colds. Kids could take a model like that and apply it to whatever they were learning–they’d be both applying their research and working on their expressive writing skills. (Not to mention actually having fun.)

Hey, you got me back on my soapbox again!

I realize that a cold germ is not an inanimate object. But it’s not a person, which is what made personifying it fun.

I agree with you whole heartedly. I’ve never been one to write an essay just for length. It’s my desire that my children write because they have something to say. I’m just dropping in today to wish you a very happy St. Lucia. I hope you are enjoying the season and you are well.

Thank you for reminding me that it was Lucia Day, Valarie! I used to remember, back in the days when Lulu was younger and loving her American Girl, Kirsten. We even used to make lussekatter.

I love this post, Patricia. My kids just had to write an essay with these very guidelines for a Charter School requirement. The finished products were so stale, and didn’t represent the brilliant voices of my children. I loved having my feelings articulated in your words. Thanks for taking the time. It was perfect timing for me.

Oh, why are these essays so rampant? I’m glad you recognize that such a formula isn’t the best way to capture your kids’ brilliant voices, Darcie. 🙂

It might be interesting for you and your kids to play with the idea of how, when freed from the formula, they could present that same content in a more captivating way. How might they do that? How might a magazine writer approach it? (Even if they aren’t inspired to rewrite, it could be an intriguing conversation.)

YES!!! Exactly. (says the former high school English teacher)

Also, one of the most common questions in the professional writing world is, “How do I find my voice?” This type of writing education completely eliminates individuality and the unique voice of each writer. Why kill something they’re going to spend years rediscovering later?

I could go on for days about this, too. 🙂

Precisely, Michelle! As an adult who set out to teach herself to write, I’ve read more adult writing guides than I can count. Every single one has a section or a chapter on finding one’s voice–because most of us did not find our voices as writers in school.

I often start my workshops for parents on writing with this point. There is something very telling in it.

(My next post will touch on the idea that we parents should try not to “kill” what our kids naturally intuit about writing….)

Glad to discover a fellow rager-against-the-essay!

And (can you tell this drives me crazy?) the formula has led people to believe “rewrite” means “line edit.” Draft, rewrite, rewrite, edit, proof. The distinctions and value of each stage are never taught, because it’s all fill-in-the-blank writing.

There. I’m done. For now. 🙂

Ooh, I love it when readers get so riled up, they come back to add addenda to their comments!

I am right there with you on this. All of it.