Do you remember writing school reports when you were, say, twelve? Do you remember your teachers harping on the evils of plagiarism? Was your response to do what I did and take lines from a book, switch out words, change their order and call them your own?

I can’t blame twelve-year-old me. Despite all the plagiarism sirens, I don’t remember a teacher showing me how to take ideas from other sources and weave them into writing of my own.

Learning to use source materials to inform original writing is a tricky skill to learn, but it’s an essential one. Most kids, even homeschooled ones, will eventually find themselves in a situation that requires it, whether that means a 4-H report, a display for a history or science fair, an essay for a class, content for an online wiki.

How do you help kids write original reports, biographies, essays and articles on topics which others have already covered? How do you help them take the ideas of others and work them into their own line of thinking?

I’ve worked out a process that has helped my kids over the years. Stacks of Post-Its are involved. You could certainly do this with index cards or scrap paper, but the stickiness of Post-Its can be useful in the organizing process. It keeps the notes from flitting about as the kids sort and arrange.

This method works best when parent and child work together, at least initially, regardless of the kid’s age. It works great for younger kids. Likewise, when an older kid is beginning a daunting project, going through the first steps of this process with a parent can get them up and running. I even used this technique to help my oldest get started on his college application essays.

This process is heavily influenced by my own experiences as a writer. In the steps below, I’ve placed a few lines in italics to point out the writerly logic behind the process.

I’m laying out a series of steps in a continuous list, but please don’t go all eager-beaver and attempt them in a single sitting! Break them up, over several days even, according to the child’s interest and maturity. Life lesson to be learned here: a big writing project is easiest when divvied into manageable parts, and spread out over time. This process will show kids how to do that.

A method for writing nonfiction based on other sources:

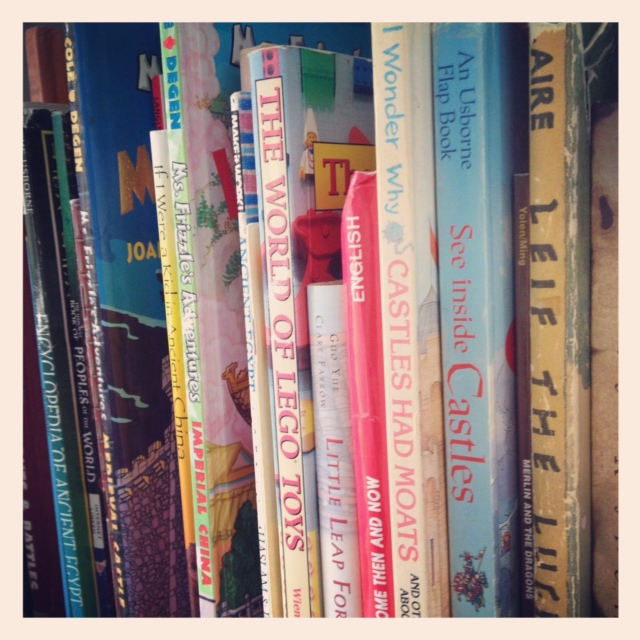

- Research your topic. Help your child dig deeply into research before he or she starts writing. Read books, but don’t limit book selection to straightforward nonfiction. Look for books in varied formats, if possible: with graphics, fictionalized information, even comics. A variety of writing styles will open up the possibilities for the child writer. Also, look for interesting websites, films and documentaries. Don’t limit research to books.

- Narrow down the topic. A report on chimpanzees is likely to be too broad, for example. With too much information to cover, the child will have to skim superficially across the topic. Focus on a particular area of interest. How chimpanzees live in groups, perhaps. If the child can’t decide what to focus on yet, do the dictation and sorting steps below, and see what interests emerge.

- Close the books and move away from the computer. It’s much easier to convey ideas in original language, and from a more original perspective, if you aren’t looking at the source material.

- Have your child dictate as much as he or she can remember about the topic and write each idea on an individual Post-It. For this step, you can have the child sit beside you, or even better, encourage him or her to move around and even walk circles while recalling information about the topic. Write down each idea on a separate Post-It. A child can certainly do this step independently, but initially it’s very helpful for a parent to take notes while the child moves and thinks aloud. Being able to move, and not being nerve-wracked by the blank page can be a big help in the early stages of a project. The child does not need to relay information in any logical order. Encourage interesting, juicy details. The child may need to consult sources for specifics later, but get the general ideas down now, in his or her own words. Be prepared to consume plenty of Post-Its! Writing each idea on a separate Post-It may seem wasteful, but it allows the ideas to remain unfixed and, literally, movable. It keeps the paper’s structure flexible, which is important at the beginning of a project.

- Re-read the Post-Its and have the child add any points that seem missing. He or she may want to go back to the source material at this point to do a bit more research, but again, encourage the child to move away from the sources and dictate any new ideas in his or her own words. If the child comes across a source quote that is particularly powerful or interesting, you can copy the quote directly, making sure to attribute the source. Once you get to the writing phase, consider using no more than one apt direct quote per paragraph. That’s a good general rule of thumb. If the child has relayed an especially interesting story or detail, he or she might want to set it aside for the paper’s introduction. More on that later.

- Sort the Post-Its into piles that seem to go together. If, for example, the child is writing a report on the contributions of Eleanor Roosevelt, she might put notes about the formation of the United Nations together. Post-It stickiness comes in handy here: the child can literally stick together notes that seem to belong together. You may need to help with this sorting initially.

- Narrow these piles of Post-Its to three or four piles—unless the project is planned to be an especially lengthy one. If there are extra Post-its that don’t fit in any piles, put them aside, and save them. The child might not need these ideas for his or her project–or he or she might try to make an additional pile for some of them because they seem particularly important. It’s okay if many of the initial Post-Its ultimately get discarded; what’s important here is that the child narrows in on what he or she really wants to convey. This step helps the child recognize which ideas matter most to him or her. The most salient details tend to cluster together, based on the child’s interests and sensibilities.

- Help the child give each pile a title that sums up the ideas in that pile. If your child is writing a history of real-time strategy video games, for example, he might title a pile “Early RTS Games.” Write the title on a different-colored Post-It, or with a different-colored ink. Have the child put these title notes on top of the appropriate piles. These are the main ideas for the child’s paper. This is an important step; having a handle on the main ideas will help the child write a clear, logically organized paper.

- Read the pile titles aloud, and arrange the piles into an order that makes sense. Which pile should come first in the paper, which second, and so on? Each pile will essentially become a paragraph, or a series of paragraphs, in the final piece. Do the pile titles fit together into a cohesive whole? Is there a logical arc from the first to the last? If not, the child might be trying to convey too much. Would it help to remove one of the piles that doesn’t seem to fit? Or to focus on a single pile, and try to expand it into separate piles? The beauty of this process is that the child is organically creating an outline, according to his or her own ideas and synthesized sources—rather than using some author’s outline, which is what kids tend to do if they write while constantly consulting source materials.

- Working with one pile at a time, arrange the individual notes in each pile into an order that makes sense. Now the child is essentially creating skeletal outlines for each paragraph. Transitional words and sentences will probably be necessary; we’ll get to those in a bit. At this point, the child might want to return to source material to add details, but once again, encourage him or her to leave the source material before rephrasing.

- Choose which pile to begin working on first. I always encourage my kids to save writing their introductions and conclusions for last: those can be the most important sections in a piece of writing, and are often best shaped once the bulk of the piece is written. The child probably hasn’t made a pile for the introduction and conclusion anyway. Skip the introduction and have the child start with one of the piles. Kids don’t have to begin with the pile that will ultimately come first, either. Encourage them to dig into the section that seems the least intimidating. Professional writers rarely work in a linear order.

- Write a paragraph. Have kids spread out the notes from their chosen pile in order. Read the notes aloud. Each note is like a pearl on a string, and each should lead logically to the next note. What words and ideas are needed to transition smoothly from one note to the next? Sometimes several sentences need to be added. It takes practice to learn how to do this. Consider taking dictation from your child as he or she constructs the first paragraph or two from the piles–or take dictation on the entire piece if it helps your child focus on the content. You can add transitional sentences to additional Post-Its, if you like, but I prefer typing the paragraph on the computer at this point. It makes it easier to change the wording as you go.

- Move or discard notes that don’t fit where your child thought they would. The paper may change a bit as the child works on it. That’s okay; writers ultimately figure out what they want to write by writing. Keep the process flexible.

- After the paragraphs are finished, re-read them. Does the writing in each paragraph flow? Do all of the sentences and details fit with the original main ideas–the pile titles? It’s okay if those ideas have shifted, but your child should be able to verbally summarize the purpose of each paragraph in a single sentence: “This paragraph tells why _________.” “This paragraph describes _________.” If the lines and details in a paragraph don’t support that sentence, or don’t lead logically from one line to the next, go back and try to tighten them up.

- Write the introduction. (Or the conclusion; order matters less than the writer’s inclinations!) The introduction should captivate the reader, and compel further reading. Did your child find an interesting story or fact when researching? Start with that! Elaborate on the idea, and give readers a sense of where they’re headed in the rest of the paper. But don’t feel a need to explain the entire piece ahead of time, with a traditional school-ish thesis statement. That makes for rather dull reading.

- Write the conclusion. This was the part I always dashed off at the last minute as a kid. Wrong! A good ending should be more than a tacked-on summary; it should contain something unexpected too, which leaves the reader thinking. Why is this person or topic important? That’s what you want your readers considering as they finish reading. If writing a compelling conclusion seems difficult, try reading the final paragraphs of nonfiction that you and your child admire, and see how professionals do it. Your child might surprise you, though: after writing an entire nonfiction piece with this process, kids usually have a firm grasp of their topic and are able to offer real insight by the ending.

Phew! How’s that for a process? Seems like a lot of work, but it’s much more effective than having a kid simply sit down and blindly write, directionless. And the early steps are fairly painless–they’re just a matter of recalling interesting information, and getting something down on paper. I think the process gives the child a greater sense of control over his or her ideas: attention is given to deciding which ideas matter, and where they fit in the whole. The process helps a child learn to write more as professional writers do.

You can use a similar process to help a child write nonfiction which isn’t based on other sources. When I helped my oldest with those college application essays, for example, he simply brainstormed random thoughts based on the essay prompts–Reflect on a challenge you overcame through persistence. Describe your dream job. Tell us which aspects of filmmaking seem of particular interest to you and why–and I jotted his thoughts on Post-Its. Then he was able to look over the notes, and sort and discard as described above, and begin to develop outlines for his essays.

If you’ve been reading this blog for any length of time, you know that I’m a fan of working with a child’s internal motivation. With writing, with everything. Therefore, I don’t recommend “assigning” a paper like this to a child. If you’re intrigued by the process here, just file this post away in your computer stacks. And when your kids come to you wanting to write that 4-H report, or that science fair display, or that wiki entry, or a history of a real-time strategy video games, you’ll have some ideas for how to help them get started.

And I’d love to hear back if you do.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Thanks for this post. It’s interesting to see a version of this for younger kids that is pretty similar to what I do with upper-grade high school students: read, think, brainstorm, sort, connect, extend, refine, write, revise.

Researching and writing are two different skill sets with discovery at the heart of each.

And I agree 100% that internal motivation is the best educational inspiration possible. When it comes to writing, the results are always better when students care about the focus of their writing.

Thanks so much for taking the time to respond, Gary. I’m always impressed with what you do with your students! My older two kids went from homeschooling to choosing to attend high school–and a pretty traditional high school at that. Both were happy with their choice, but the formulaic writing instruction at the school is enough to make me cry! (Which is why I had to help my oldest with his college app essays–just two years of high school English classes actually undermined all he’d once known about how to write well.)

I wish all school kids could learn to write in classes like yours. Keep writing your books and spreading your ideas!

Great post Tricia. You nailed the process so well that immediately found myself floating around in fantasy land thinking how great it would be to assign Jesse a non-fiction writing project so that we could follow your well defined road map. Thank you for your last paragraph which brought me back down to earth. I am sure their will be opportunites to do this type of writing with Jesse…if I keep my eyes open for them.

Also- the Brave Writer curriculum has a really great activity for narrowing down big topics into more managable size ideas…I think it is called the topic funnel. Maybe I can share it with you on Friday after writer’s workshop.

Well, I don’t recommend “assigning,” but you could certainly suggest. The example I used about real-time strategy games came from a current interest of Mr. T’s. He’s been researching and talking about the different types of video games nonstop lately. I showed him this post and mentioned that if he wanted to write a report about real-time strategy games, we could try it. He seemed interested. So, we’ll see!

(Just have to get that blog attached to our support group website so the kids can share their writing there!)

I remember you mentioning the topic funnel idea. Would love to hear more about how you’ve used it.

Thanks for this informative post. While my son will take a while to get to this stage, your process is what I used when writing Uni assignments. So I am keeping this filed away to help me teach E at a later stage. (Hope you don’t mind but I linked it to my blog because I haven’t seen anyone else tackle this subject in such a common sense and approach. Let me know if not.)

thanks!

Interesting that you used a similar process in college, Paula. I think many of us figure out techniques like this eventually, if we do a lot of writing. Experience helps us figure out what works! It’s great if kids can learn to think like this when they’re young, so they don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

Do I mind if you linked me on your blog? Ha! Links are what keep the conversation going here. I would hug every person who links me if I could reach them!

Hi Tricia,

I’ve used this technique before too, the post-its and the adding to them, etc. I think I learned about it at the HSC conference a long while back. I used it with my eldest numerous times and it worked!

In fact, before we travelled to Belize, I did assign a paper (because he was in middle school and willing) and you’ve heard it in your writer’s workshop. He chose the subject matter. It was about the coral reef. Remember?

Anyway, I think your process would be valuable to anyone who needs to write in that format and needs a refresher about how to get started.

How interesting that you learned a similar technique at the conference, Kristin! I picked up a simplified version of the Post-It idea back when I was teaching, from some fabulous older, yet very progressive teachers in my school district. (Loved those ladies!) Of course, the kids in my class did the note-writing on their own, but I think there can be something very powerful in the dialogue between parent and child. Many of the steps above revolve around that conversation.

I definitely remember O’s paper. It was memorable!

I loved this post. My almost 16 year old is just learning now how to write a five paragraph essay in order to pass the test required to take classes at a local community college. He never wrote a paper until now; I know an essay is a bit different than a paper — the reality is that kids need internal motivation in order to want to develop any of those skills. Now he has the motivation to learn how to write and what to put in it in order to satisfy the tester’s requirements….

My older son, almost 18, developed writing skills when he wanted to have his own blog and sound professional. He and I worked hours on his writing skills and next month he is signed up to take the SAT — he took that practice test (that has a 5 paragraph essay as part of it) on line at the SAT website and scored much much higher than I ever would have guessed possible, knowing what he did/didn’t do writing-wise.

Now my 7 year old is just deciding that he wants to write — notes to us when he is in the car. Love it!

Love your blog too.

So neat to hear how different kids become inspired to write, Cathy, and how it happens at different ages for each of them. Writing blogs can be particularly effective, if the kid wants to do it, because there’s potential for an audience. As you and your son have figured out, I’m sure!

It’s always fun to hear what your kids are doing.

thanks for the info. i wished i had these ideas when i was growing up. this is the beauty of homeschooling. i get to learn along with my kids. love it!

Absolutely! Sometimes I wonder who is learning more–my kids or me!

I just realized that you’re Park Day Maria! Thanks so much for taking the time to comment.

Patricia, this is great stuff. Thank you for sharing.

My pleasure, Renee. Thank you for reading!

post-its are precious tools. i used them waaaay back when i was in graduate school and was trying to get a handle on the theoretical model i was examining for my dissertation. post-its kept things short and simple and very movable – quite necessary as i discussed/argued/defended with my chair! i’m glad for this reminder about using them – i have been into using index cards with my kids because they work well in shifting things around on the floor, but post-its are awesome for dry-erase boards and wall space and big posterboards.

here’s one of my personal challenges. i’m a scientific writer by training and am finding it extremely difficult to let go of the approach and style i learned in favor of letting my daughter discover her own way. it’s not an issue with her creative fiction, because i’m completely hands-off with that, other than being an appreciative audience. how do i provide the process assistance to her (which she does need, because she’s overwhelmed and confused when faced with non-fiction writing) without taking over the project and having her write it the way that i would?

i should add that i’m not particularly confident about my own writing, despite my experience, so i’m not terribly convincing (or convinced) about my capability to guide her in this.

your thoughts and perspective are most welcome on this. your words mean so much!

Love those Post-Its!

Have you tried using a process something like what I describe above, Dawn? The neat thing about such a process is that it helps the child figure out what aspects of a particular topic are most interesting to her. If you go through all of the steps above, the piece will begin to take its own shape. It might be easier to support your daughter in this way, because her own ideas would help dictate how the piece should be written.

Also, perhaps you could help your daughter find nonfiction books that she particularly likes. She could find a favorite and use it as a model–even if she were writing on a different topic. In other words, rather than writing a traditional essay or report, or rather than you inadvertently pushing a scientific-writing style on your daughter, you could help her try to mimic the style of her admired writer.

One of the projects I’m slowly working on is compiling a list of excellent nonfiction writing for kids. There’s so much good stuff out there now, and that’s what kids should be modeling their own nonfiction on. That’s so much more exciting that following some formula for a 5-paragraph essay!

Oh, and this book is full of ideas for exploring nonfiction topics in a fun way: 51 Wacky We-Search Reports by Barry Lane. It isn’t a book on report or research writing; rather it’s a collection of fun explorations. Still, it might offer ways of pursuing nonfiction in a style different than the scientific writing you’re used to. The book is written for kids, and kids tend to like it.

Please let me know how things go with your daughter!

This is such an amazing post that I’ve saved a copy on my computer in case your website disappears. Thank you so much!

I won’t let my website disappear, Jen, promise! But I’m honored that you like the post so much. I gave a workshop for kids and parents yesterday on just this topic, and it was so neat to hear the giddy enthusiasm throughout the room as kids dictated their ideas to parents.