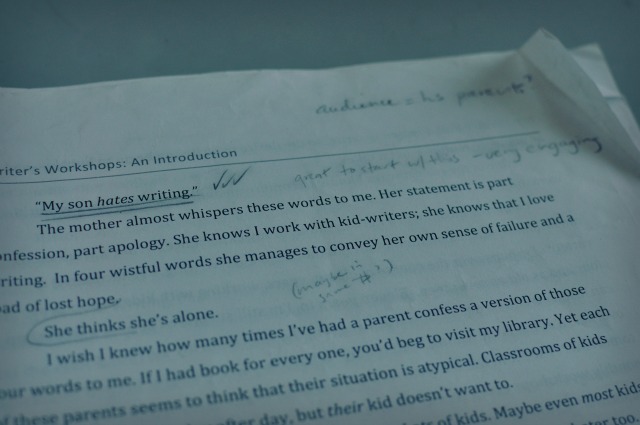

Feedback on my book’s introduction from one of my longtime reader-friends.

You may have read this post already, as I shared it as a guest writer on the Spilling Ink Creativity Blog. I thought I’d post it here as well, in case some of you missed it, and so I can link it with my other writing with kids posts.

The piece was written for the young people who are the central audience for Spilling Ink, so it may read a bit differently from my typical post here. Some of these tips may help parents who hope to give feedback on your kids’ writing. Still, I think that feedback from a parent to a child is a slightly different, potentially fraught endeavor–so I’m planning to write a short series on parents offering writing feedback in the new year. Stay tuned.

Oh, and the wonderful Annie of Bird and Little Bird has a lovely review of my book, and a giveaway on her blog this week. If you haven’t discovered Annie’s e-magazine Alphabet Glue, you are in for a treat. It’s packed with projects and fun for families who love books!

* * *

5 Tips for Offering Feedback to a Writer

If you are the sort of writer who writes for an audience—meaning you’re not simply writing in a journal, or writing stories about your cat for just you and your cat—you might appreciate getting feedback on your writing from others. Feedback can be useful and encouraging and validating. It’s often just the thing a writer needs to move from one level of writing to another. It can offer the difference between feeling like you’re reading your work into a deep canyon and hearing nothing but the echoes of your own voice in reply, and feeling like you’re reading your work at a campfire beside that canyon, with a circle of captivated listeners, who roast marshmallows and urge you on.

There are many ways to get feedback on your work. You might gather a group of fellow writers—or even one writing friend—and take turns sharing your writing and offering one another feedback. Such a format is sometimes referred to as a writer’s workshop, or a writing club, as it is here on Spilling Ink. There are ideas for starting your own club here on the Spilling Ink website. If gathering with other writers proves difficult, you can try sharing your work with one or more readers via email, and asking for written feedback. I received some incredibly useful written feedback on drafts of my new book from friends I’ve gotten to know online—people whom I’ve never met in person. Or you might share your work with others in writing and then “meet” to discuss it using a platform like Skype. When one of the women in my own writing group moved away, we began having her join our meetings via Skype, and it’s worked surprisingly well.

Feedback can be a tricky thing. It’s like bacteria: the right type is good for you, like the microscopic organisms in yogurt, but the wrong type proliferates in your gut and has you running to the toilet! The right kind of feedback encourages a writer, and inspires you to keep writing. Too much misguided, critical feedback, on the other hand, can discourage a writer, and make you wish you’d never shared your work in the first place.

After years of participating in writing groups myself, and facilitating writer’s workshops for kids, I’ve gathered some tips for offering the useful, encouraging kind of feedback to a writer. If you’re in a position to respond to the work of other writers, you might keep these tips in mind. And if you share your work with others, you could offer a copy of this list to make sure you receive the sort of feedback you need.

5 Tips for Offering Feedback to a Writer:

1. Focus on the positive. When it comes to giving feedback, people often treat positive remarks like a quick introductory handshake. They’re the polite gesture that precedes the “real” feedback: the honest, constructive, critical stuff. Hold it right there! Positive feedback may be more powerful than you realize. It’s important for writers to hear what we’re doing well—because we don’t always realize what we’re doing well. It’s difficult to have perspective on our writing from where we sit behind the pen or the keyboard. Positive feedback gives us that perspective; it helps us see our strengths as writers. And when we understand what we’re doing well, we can keep doing it. That’s what it takes to improve as a writer.

When offering feedback, tell writers which parts of their work capture your attention. Point out words and lines that seem original and special. When you say that you like something in a piece of writing, try to explain why you like it.

Your positive feedback can help a writer see how much he or she already knows about writing. It can inspire a writer to keep writing.

Don’t underestimate positive feedback’s power.

2. Don’t try to rewrite another writer’s work. When given the chance to offer feedback, people often resort to telling how they would write someone else’s piece. It’s simply easier, I think, to recognize “flaws” in the work of others than it is to see what ought to be fixed in our own work. As Tip #1 states, it’s challenging to have perspective on our own writing. We can’t always recognize what isn’t working. Because it can be such a challenge to revise our own work, shaping someone else’s writing can seem easier! More satisfying!

Rewriting another writer’s work is not your job as a responder, however. In a feedback session we should not be telling other writers how to change their work. It would be more useful to point out what the writer is doing effectively—and to offer constructive feedback carefully and sparingly. Which leads to my next tip.

3. Keep constructive feedback concentrated on a few specifics. Too much constructive feedback can overwhelm a writer. When readers suggest how to write a piece differently, it can muddy a writer’s own vision of the work. Instead, consider responding to two simple questions: What confuses you in the piece? What would you like to know more about? Focusing on these two questions concentrates your feedback on the writer’s words, rather what you would do with those words. Responses to these questions are likely to be useful, without seeming like you are attacking the writer’s work.

4. Let the writer’s questions guide the feedback session. The best way to insure that writers receive the feedback they need is to let writers ask for what they need. Before sharing work with others, a writer might consider what he or she wants help with, and assemble a list of questions. Did I give enough evidence to convince you that Marvel is superior to DC? What did you think about the zombie at the gas station? Did you believe in the friendship between the exiled princess and the ferret pilot, or do I need to add another scene or two? Questions should be complex enough to require readers to think, and to force them to respond with more than a simple yes or no. And if a writer really wants to know how readers might rewrite the work, or part of the work, he or she can ask.

5. If you’re giving feedback in a group, consider using the Cone of Silence. This tip applies whether your group is meeting in person or via video. I learned about the Cone of Silence in one of my adult writing courses. Basically, you begin a feedback session by having the writer read a favorite paragraph of the work aloud. (Or the writer may read the entire piece—if readers haven’t seen the writing already—as we do in my kids’ writer’s workshops.) Then an invisible cone drops over the writer, and he or she can’t speak until the end of the feedback session.

This method is helpful for a few reasons. First, feedback sessions are likely to linger on and get bogged down if writers continually explain and defend what they’ve attempted to do in a piece. Even more important: if listeners are confused by any part of the work, the writer’s silence forces them to work together to tease out what confused them. The writer can hear how different readers interpreted the writing, which can be very instructive.

Towards the end of the feedback session, the cone should be raised so the writer can ask those essential questions posed in Tip #4.

* * *

One of the most important things to remember about feedback is that you can learn as much by giving it as you do when you receive it. Offering feedback to another writer helps you pay attention to what works and what doesn’t work in writing. It helps refine your ideas about what kind of writer you want to be.

If you’re serious about writing, consider finding another writer—or two, or five—and sharing your work with one another. It’s likely to be more encouraging than reading your work to your cat, or into an empty canyon. And whether or not s’mores or campfires are involved, the feedback you give and receive is likely to fire up your writing in ways you hadn’t imagined.

As I think I’ve mentioned before, I teach writing (both composition and creative writing) for a living–but your suggestions here are crucial reminders for me; as I am feeling overworked (which is most of the time) and pressured to see fast improvement in, say, a first-year composition student, I have begun to do some rewriting (so easy when I’m responding via computer–ugh), and I skip to the tips too quickly, shortchanging the praise. I’ve also forgotten how easy it is to overwhelm a developing writer with too much feedback. I’m printing out your tips and posting them next to my computer. Thank you, madame. 🙂

I think it’s human nature to skip over the praise and jump into making suggestions and rewriting the work of others, Melissa, don’t you? Just ask the women in my writing group–I’ve had plenty of *great* ideas for rewriting their work over the years! And there’s certainly value in hearing helpful, constructive feedback from teachers and mentors and other writers whom you admire. But it’s easy to forget how much we can learn from specific, insightful positive feedback on our work, and a few carefully chosen suggestions for expansion or clarification.

I have to remind myself of this all the time, too.

I’m running a workshop for writers ages 6-13 right now, and I have really been trying to keep your suggestion to focus on the positive in mind. When I was teaching, I was much more aggressive about “correcting flaws,” as I saw it, and I’m realizing that approach was overwhelming to a lot of students. In my writing group, I noticed that when I made a suggestion for improvement, such as pointing out words that writers could make more specific in their writing, I could feel them kind of withdrawing emotionally, perhaps to defend their ownership of their writing and not let me take it over for them.

It works SO much better to show people what they’re doing well and help them build on that–it’s the approach I respond best to when I’m getting feedback. And I agree that keeping the questions more general, such as asking “Was there anything you want to know more about?” or “Was there any place you were confused?” is so much helpful, and lets the writer decide how they can correct problems.

I like the Cone of Silence idea. I also have liked using another idea of yours from “Workshops Work,” which is to let the writer be the one to call on people to give them feedback, rather than have me be the one to call on people. So much more empowering, I think. Thank you for all the good info!

Carrie, I know just what you’re talking about when you say you can feel kids withdrawing emotionally when you’ve made even a small suggestion for improvement. It’s almost as if you can see them pulling into their shells a bit. It’s interesting that I don’t notice that same body language when writers ask for specific help, and readers offer it. Those writers seem to be in a place in which they’re open to suggestions, and it makes a difference.

Wow, your group has kids from 6-13? I’ve never worked with such a big age span. At some point I’d love to hear more about how that works for you!