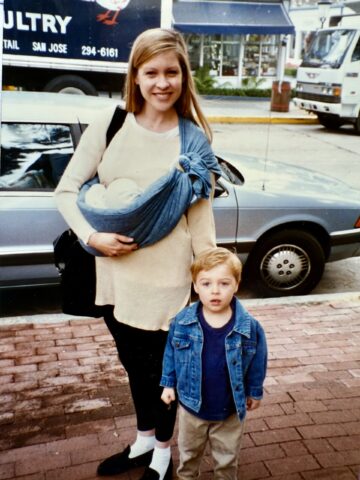

1995, in my early Over the Shoulder Baby Holder® days

Dear fellow wonderer,

A stat to consider:

There were five times as many parenting books published in 1997 as in 1975, when the word “parenting” was not yet a classification and books about childrearing were listed under “Children–management.”

–Anne Cassidy, Parents Who Think Too Much (1998)

Why would a ’90s shift in parenthood matter, you may ask, all these years later, in 2025?

I’ll tell you why. This shift in parenting norms–and the use of “parenting” as a word–set off a cataclysm of shifts, shifts that are still playing out in our culture to this day.

But to get there, let’s go back.

* * *

In 1997, I was the mother of a five-year-old with Dennis the Menace hair and a knocked-out front tooth and an almost two-year old with dimples and a whiskey voice. A prime candidate, I was, for all those ’90s parenting books.

I had a shelf of them. During my pregnancies, I’d gagged down vegetables in the early months because What to Expect When You’re Expecting had laid out how many I must consume, down to the color: green, red, orange. My baby’s successful odds depended on “each bite!”

I had Brazelton, I had a bunch of Waldorfy-books, I had the Searses. Oh geez, the Searses. You know you should be suspicious when you see a title like The Baby Book: Everything You Need to Know About Your Baby from Birth to Age One.

Everything! The audacity!

I’d also been a ten-year-old back in 1975, and I remember precisely how many childrearing books sat on my own parents’ shelf. One. One old paperback copy of Baby and Child Care, by Dr. Spock. The one with the pink-cheeked grinning baby, propped on chubby arms. The one that famously says on the first page, “Trust yourself. You know more than you think you do.”

That must have been all my parents needed to hear. I don’t remember that book ever moving from that shelf.

* * *

The ’90s rise in parenting books is an interesting development. Journalist Ann Hulbert tracks the rise in Raising America, her 2003 overview of 20th century parenting “experts.” Sounds dry, but Hulbert keeps things moving with her wind-up baby swing of a book that rocks back and forth for a hundred years, back and forth between “parent-centered” experts who espoused discipline, and “child-centered” experts who promoted family bonding.

In the mid-’90s, as parenting books were multiplying five-fold, the “parent-centered” faction got The Seven Habits of Highly Effective Families by the likes of leadership guru Stephen R. Covey, while the “child-centered” folks got multiple books from Dr. Stanley Greenspan, full of, according to Hulbert, “charts and a managerial outlook.” Hulbert notes that “where Spock, pragmatic and companionable to the core, had done his best to buck up mothers–and fathers–with assurances…his successors were ready with much more programmatic wisdom.”

These books were all formula, all business model, the new norm in parenting manuals. The “experts” seemed to believe that more mothers in the workforce meant that mothers now wanted to run their families like corporations.

I was definitely on the child-centered side of the swing–more on that in a minute–and I didn’t own any of those Highly Effective books, but I do remember feeling a sense of failure that we weren’t having family meetings. Family meetings! As if all our dinners together, that noisy thrall over spaghetti and broccoli, Chris and I listening, the kids railing on about their Tomagotchis and hollering, “It’s my turn to talk!” didn’t count as meetings. Somewhere, somehow, despite not owning these books, I’d internalized their message: I should be running my family like a business. Setting a regular agenda. Making sure that in bulleted order, each family member’s concerns were heard.

* * *

Until recently, I never thought deeply about how I was a different sort of parent than my own parents had been. Then one morning about a year ago, I was researching intensive parenting, a term all over the media these days. These stories often mention the term’s origins, a 1996 book called The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood, by sociologist Sharon Hays.

Of course, I didn’t think of myself as an intensive parent. I’d been a parent who valued independence and agency for my kids! I’d homeschooled with them to tailor their learning to their interests, to allow them creativity!

Intensive parents push their kids, over-schedule their kids, do too much for their kids, expect too much of their kids. Right?

And then I read a line in Hays’ book that literally stopped me in my tracks. (I’d been skimming the book while pacing circles around my kitchen, getting in some steps.) Referring to mothers in 1996 (me!), she writes, “The methods of appropriate child rearing are construed as child-centered, expert-guided, emotionally absorbing, labor-intensive and financially expensive.”

Child-centered was the term that stilled me. My parents hadn’t believed in child-centeredness. Sure, they loved me, fed me, clothed me. Like many mothers of her generation, my mom put out a plate of Hydrox cookies, Tupperware cups of Kool-Aid and said, “Go outside and play.” My dad read to my brother and me, I remember that, but no one seemed to be thinking about how I learned, driven by the notion that they should center me.

But I’d been a teacher in the early ’90s. Child-centered had been my credo.

Holy shit, had I been an intensive parent? I considered Hays’ other descriptors. Which brings us back to expert-guided and all those books on my shelf.

* * *

When I was pregnant with my second child, I’d become newly interested in baby slings and bought that audacious 767-page behemoth The Baby Book by Dr. William Sears and his nurse wife Martha, fellow parents of eight. This book, published in 1993, would become known as the “attachment parenting bible,” the go-to for parents interested in the “gentle bonding” side of Hulbert’s expertise swing.

I recall the book’s heft and how I highlighted many pages in pink. (I just liked pink–I had no inkling I was carrying a girl.)

How I wish I still had my copy of that book. Wish I could flip those pages, interpret my highlights. What expertise had the Searses imparted that made such an impression that I felt compelled to trace it in ink?

I liked attaching my new baby girl to myself via my Over the Shoulder Baby Holder, despite its cringey name. But I recall reading other parts of the Searses’ advice with narrowed eyes. Their thoughts on pacifiers, for one. I’d used a pacifier with my oldest. He’d called it a nunnie and it helped him sleep. And this new baby: I’d pop her in the sling, pop in the pacifier, and she’d be out.

Since my original copy of The Baby Book is long gone, I find a copy of that first edition, search for pacifier in the index, discover this: “To insert the plug and leave baby in the plastic infant seat every time he cries is unhealthy reliance on an artificial comforter. This baby needs picking up and holding.”

What?! Look at the phrasing here! The Searses don’t simply use the word pacifier–no, they call it “the plug,” implying that I’d want to plug my baby, shut her up. They don’t use the phrase infant seat–no, they call it a “plastic infant seat,” spotlighting artificiality, adding a layer of shame. They don’t refer to occasional pacifier use–no, they jump to the assumption that I might “leave” my baby “every time” she cries. For a parenting style aligned with attachment and gentle bonding, these lines bellow judgment and condescension.

“This baby needs picking up and holding.”

How did they know what my baby needed? And then consider how later, Dr. Sears (presumably) writes about appointments with young patients: “But in defense of the much-maligned pacifier, I soon relax my unfair judgment of the rubber comforter as baby sucks contentedly during the entire exam.”

Can you hear me growling? Apparently as a mother, I should feel guilty about using an “artificial comforter” but pacifiers are fine when Dr. Sears has work to do?

I’m proud of my young mother self for using pacifiers anyway. For deciding the family bed was not for us, despite the Searses’ guilt-shaming insistence. But I sure wish after I’d read those pacifier lines, I’d shoved aside my highlighter and chucked that book across the room.

* * *

Along with Covey’s seven habits and Greenspan’s “five principles of healthy parenting,” the Searses propounded “The Seven Baby B’s” of attachment parenting. To “breastfeeding” and “baby-wearing” and “bedding close to baby” can I add barf? I mean, their childish alliteration is patronizing, like mothers aren’t smart enough to remember important points without mnemonic help–but even more, I reject their assumption that their very specific formula will lead to a certain outcome: a “happier and healthier” child.

Not to mention the pressure the Searses’ formula put on mothers. To be constantly there for their baby’s every need: strapping them on and breastfeeding them and sleeping with them while also feeling guilty about any plastic contraptions, well. It’s no wonder mothers began to believe that a new sort of motherhood was expected, an intensive sort of motherhood.

Five times as many parenting books in 1997. Just consider the formulas these “experts” were shilling and consider Hays’ 1996 list of shifting beliefs: “The methods of appropriate child rearing are construed as child-centered, expert-guided, emotionally absorbing, labor-intensive and financially expensive.”

Beyond just “expert-guided,” consider how those “experts” were pushing the other new norms on that list.

* * *

My daughter loved her nunny. She loved it so much that when she went to sleep, she demanded an extra in her hand, in case she misplaced the first.

Eventually she wanted one for the second hand, too.

Ridiculous to assist this, I knew, but otherwise she was a deep sleeper. Her nunnies gave her comfort. Did I feel guilty about this? How could I not, after being shamed by the Searses–those attachment parent “experts”–about the plastic plug? They’d gotten in my head. Only for sleep did I allow my kids pacifiers. I didn’t let them walk around, sucking, didn’t want to be judged by the attachment crowd.

When she was two, I tried to wean my girl from her nunnies. One night I prepped her, told her she didn’t need them, told her I’d hold her hand until she fell asleep.

She cried and cried and cried, bereft. I gave them back, grateful that no other parents were watching and, phew, especially no Searses.

* * *

So how did this mid-’90s shift continue to force change? Consider another mid-’90s shift, a little thing called The Internet. Once the “experts” had their 5x hooks in motherhood, just recall what happened once they weren’t confined to books.

Expert advice became more monetized, mixed with selling stuff. Think BabyCenter and its weekly “expert-approved” updates that came with links to purchase, say, a Slumber Bear (battery-operated teddy that emitted “authentic womb sounds.”) Then we got “mommy blogs”–a term I despise–which moved beyond a platform for honest talk between mothers, to more monetization and a new kind of “mother-expert.” Which a few years later led to Instagram and the moneyed cult of the momfluencer. (Yes, we’ll delve into these shifts in future newsletters.)

That’s a lot of people with a lot of money vested in telling mothers how they ought to be mothers.

Suffice it to say, in thirty years we’ve come a very long way from Trust yourself. You know more than you think you do.

* * *

One night when my daughter was almost three, she came to me and dropped her passel of pacifiers into my hands. She said, in that gruff little voice, “I don’t need these anymore.”

And that was that. I was stunned.

No “expert” told me how to make this happen. I’d just trusted my girl when she’d cried and conveyed she wasn’t ready. And she’d lived in that trust and trusted herself to choose her timing. She never asked for a pacifier again.

If we want our kids to trust in themselves, we need to trust ourselves. The rise of “experts” undermines this. I’m a reader, a researcher, a curious person who loves to learn–I get the lure of expertise. Still, it can be a powerful, stealthy, money-driven force that we need to learn how to recognize. We can use expertise to get ourselves thinking. We can also chuck that advice across the room, and find our own way.

Truly,

Patricia

I’d love to know, whether or not you’re a parent: how have you (or have you not) bucked the “experts” when it came to kids?

cross-posted on Substack