Dear fellow wonderer,

Do you know how different public schools were 30 years ago? When I tell someone I’m writing a book about how much childhood has changed, about how much independence kids have lost, the person often assumes I’m talking about freedom out in the world, how kids can’t roam neighborhoods and play outside as they once did. True: I’m writing about that. Sometimes they guess I’m writing about how much more scheduled kids are, that they have less free time. True again; I’m writing about that, too.

What they rarely assume, and what I almost never see covered in media stories about childhood change, is how much independence kids have lost in public school classrooms.

Let’s talk about that.

I once pitched an op-ed about this and an editor wanted proof that education was as different as I was claiming. Proof? How to prove an entire pedagogical shift? And then I dug up a janky page, a paper from 1993 that someone had copied and uploaded.

Janky but excellent

Learner-Centered Psychological Principles: Guidelines for School Redesign and Reform. This was the work of a Presidential Task Force–tasked by the President of the American Psychological Association, not the President of the United States, but still, a big deal. A copy of this very paper appeared in my school mailbox in (pre-inbox) 1993.

And while this paper is presented as redesign and reform, know that this is exactly how I’d been taught to teach during my credential studies a few years before. This is how I was allowed to teach in my classroom and these methods were pretty widespread in my school district. As the paper notes, “These principles are already implemented in exemplary classrooms.”

These principles, twelve of them, describe what learner-centered learning looks like and why it matters.

But first you need to understand how much this would change just a few years later, in 2001, with the passing of the No Child Left Behind Act. In a future newsletter we’ll delve further into the act–there’s so much to talk about–but meanwhile, know that the act’s focus on textbooks, standardization, and testing would undermine every principle laid out in this paper.

{Sigh.}

Let’s dig into a few. I’ll paraphrase.

The more you bring students’ interests into the process the more they’re going to learn. Duh, right? I want to tell you about the writer’s workshop we had almost every day in my third-grade classroom. That workshop embodied so many of these principles, like this one. During the workshop students could write about whatever they desired. You know, martian limericks, weekend memoirs, their adventures as a Power Puff Girl–whatever!

Their interests, the focus.

Were my students into this? They were.

Curiosity, creativity and higher-order thinking are stimulated by relevant authentic learning tasks of optimal difficulty and novelty for each student. One of the beauties of the workshop model is that it worked for students of varying abilities. One kid might rip through pages of lined newsprint telling a tale about a motorcycle trip with their dad, while another wrote a brief paragraph with a drawing of their dog–a victory. A Spanish-speaking student could write about midnight on Christmas Eve in their native language and get another student to help them translate. And because they were writing on topics that mattered to them–authentic learning task!–they pushed themselves.

Children learn best when material is appropriate to their developmental level and is presented in an enjoyable and interesting way. I think about how we’d start many workshop sessions with a picture book on the carpet. Kids almost always love read-alouds, so long as the book is engaging and at their level. Lucky me as a teacher back then: I didn’t have to use the third-grade state-sanctioned (boring) language arts text. I asked my principal if we could skip buying those texts–textbooks cost a fortune–and use that money for real books instead. No can do, he told me, but he let me leave them alongside the brooms in a supply closet to make more space for real books on my classroom shelves. Wasteful, but: ha!

Since learners come from different backgrounds and experiences they will organize information in ways that are uniquely meaningful for them. What my principal did next: he approved the grant I wrote for buying books aligned with my students’ cultural backgrounds. Decades later, I still remember the light at Cody’s Books in Berkeley on an afternoon that felt like Christmas, when I selected and stacked and filled my arms with books that mirrored the lives and faces of my students. Back in the classroom, when I read aloud those stories, their stories, those faces glowed. These were stories that encouraged my students’ own stories.

Students are encouraged to find their own ways of thinking and problem solving. I’d learned about the workshop model during my credential studies, but really dug into it one summer, over a six-week intensive with the Bay Area Writing Project at UC Berkeley–which my school district paid for. I still have the inquiry paper I wrote for that program, about how I wanted to teach my third graders to study the craft of writers we read together in class. “I want my students to come up with their own original sense of what quality writing is,” I wrote. “I want them to know which authors to go to for inspiration and then, perhaps, their writing will begin to reflect their taste, their style.”

Third-grade writing instruction aimed at developing a kid’s own style! This makes me a little teary now, knowing how No Child Left Behind and all the mandates that came later would make writing a series of standardized skills to master and belch out in five formulaic paragraphs.

Learning is facilitated when the learner has an opportunity to interact with various students representing different cultural and family backgrounds, interests, and values. A big part of the workshop model is having kids give feedback to one another on in-progress work. My students often did this in pairs, sprawled across the carpet, a particular delight. We’d end the workshop with a few students reading their work from the Author’s Chair. Think about it: since they were writing on topics of their choosing, their different cultural and family backgrounds, interests, and values were being shared with one another on a daily basis.

Pretty much the opposite of a world where textbooks are whitewashed and books about marginalized groups are being banned from schools and libraries.

Individuals are naturally curious and enjoy learning but intense negative cognitions and emotions, e.g.: feeling insecure worrying about failure, being self conscious, or shy thwart this enthusiasm. Another beauty of the workshop is that students could share their work with others, or have it be a more private act. We worked hard to create a safe, encouraging space in the workshop, and most students eventually looked forward to reading in the Author’s Chair.

On the other hand, I think about the pressures of testing, and what that may be doing to kids and their worries about failure. A friend told me recently that her son had to miss a school party because he’d taken “too long” on a standardized test; he had to finish test sections in a separate room while the other kids were celebrating. In what world does that help a kid learn? And isn’t learning the point of their education?

There are other principles in the paper; you can read the rest here. And an updated 1997 version here.

* * *

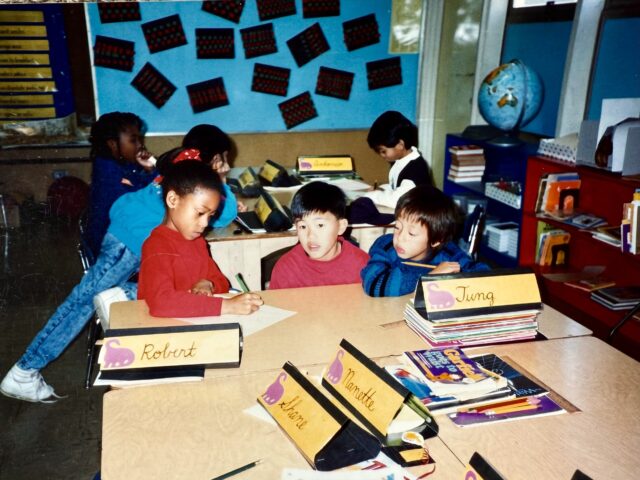

I use the writer’s workshop as example because it was the favorite part of the school day for me–and for many of my students. But these learner-centered practices were commonly used in all subjects at that time. In math, my students tackled juicy problems and discussed in groups various means to solutions, landing on their own approaches. In science, social studies, art: the same. Collaborative methods, hands-on methods, student-centered methods.

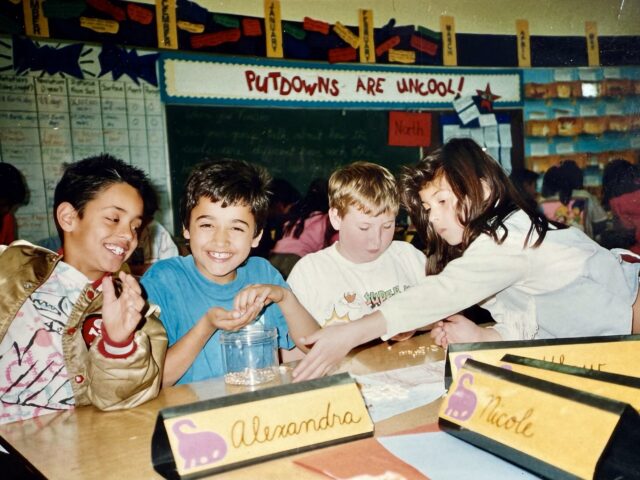

Doing something collaborative with seeds. Also: putdowns are uncool!

These Learner-Centered Principles seem so obvious to me, so basic. Of course people will learn better when they’re interested, doing work that’s authentic, developmentally appropriate, and that values their backgrounds and experiences.

But when I talk to people, I realize: if you weren’t working in education at this time, you may not realize how widespread this sort of thinking was in public education–or that it would soon be snatched away. Like I said, we’ll look more at The No Child Left Behind Act in a future newsletter, but here’s a teaser: Learner-centered education would be “singled out as a social menace that can be vanquished only by applying a rational, results-oriented and business-minded approach to public education.”

A Liberal social menace, to be clear.

Learner-centered education as a social menace! Perhaps you feel my blood boiling through the screen. As I’ve said, there’s lots more to say.

When I talked about this on a TikTok video, there were almost 400 comments–admittedly, many were my responses–mostly from teachers. While a few said that they’re still able to used learner-centered methods in their classrooms, the majority are comments of shared hand-wringing frustration. Like, “This is why I left teaching–they’re forcing us to do things that go AGAINST the SCIENCE OF LEARNING!”

And: “Can you imagine teaching with the learner being at the center of the process being controversial?”

No, I cannot. And yet, here we are.

Readers, please share your thoughts. If you’re a parent, a teacher, or someone else who works with kids, I’d love to know: how do you see learner-centered practices playing out in your kids’/students’ educations? Do the teachers in your kids’ lives seem free to teach with these practices?

Or, as in our writer’s workshop, write about whatever your heart desires!

Truly,

Patricia

Cross-posted at Substack.