About a month ago, I flipped open a book I’d requested at the library. The front flap introduced itself like this:

“Most of what you think you know about writing is useless. It’s the harmful debris of your education—a mixture of half-truths, myths and, and false assumptions that prevents you from writing well.”

I had a feeling I would like the book very much.

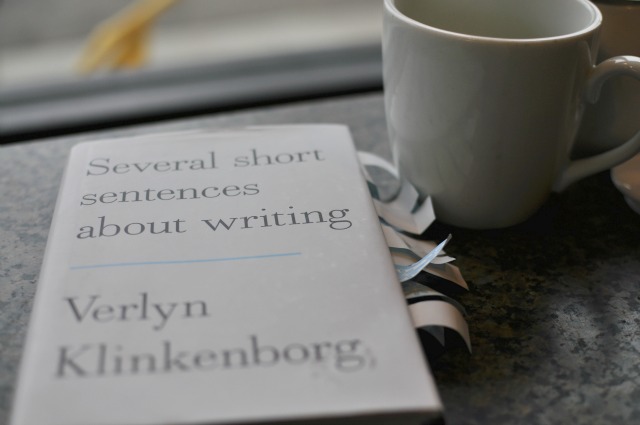

I’d requested Several Short Sentences About Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg because it’s a book of writing encouragement for would-be adult writers. As a self-taught writer, I’ve learned a great deal from such books. And this is a lovely little one, written in a unique style almost like a prose poem. I began festooning it with page flags immediately, since I couldn’t use a highlighter in a library book. The first flag found itself here, on page one of the prologue:

“What I’ve learned about writing I’ve learned by trial and error, which is how most writers have learned. I had to overcome my academic training, which taught me to write in a way that was useless to me (and almost everyone else).”

This is how I learned to write, which is why I call myself self-taught. Hooked, I read on and came to this:

“With luck you were read aloud to as a child.

So you know how sentences sound when read aloud

And how stories are shaped and a great deal about rhythm,

Almost as much as you did when you were ten years old.”

Read that again. You know almost as much as you did when you were ten. The point being, of course, that kids who grow up in homes rich with literature intuit what makes writing work. A point, you may notice, that I’ve been trying to drive home here on the WonderFarm. It did not take long for me to recognize that this book might be useful to people other than would-be writers. It might be useful to parents. The sort of parents who, perhaps, read this blog.

“Children read repetitively and with incredible exactitude.

They demand the very sentence—word for word—and no other.

The meaning of a sentence is never substituted for the sentence itself.

Not to a six-year-old.”

I know that you are all the sort of parents who indulge your kids by re-reading picture books until your eyes blur. So I know that you know this is true. Klinkenborg is saying that children understand writing beyond superficial meaning. Children value each single word and the role it plays.

Children intuitively think like writers.

Klinkenborg on what likely happened to you in school:

“You were also learning to divorce your experience as a reader

From your inexperience as a writer.

When what you needed most was to trust your experience as a reader.”

I began to think of all of the homeschooled kids I’ve known, who did not write much as young kids, but who suddenly took on writing as pre-teens or teens, and displayed a skill that belied the inexperience behind it. The inexperience with writing, that is. These were kids who had a good deal of experience as readers. I’m guessing they still trusted that experience.

Suddenly I realized that Mr. Klinkenborg was saying, in a most lyrical way, many of the same things I have tried to tell you, in posts like this.

I bought my own copy of his book so I could use my highlighter like I itched to.

“Were you asked to write in order to be heard, to be listened to?

Asked to write a piece that mattered to you?

Was there ever a satisfactory answer to the question,

‘Why am I telling you this?’

Besides ‘It’s due on Monday’?You were taught the perfect insincerity of the writing exercise,

Asked to write pieces in which you didn’t and couldn’t believe.

You learned a strange ventriloquism,

Saying things you were implicitly being asked to say,

Knowing that no one was really listening.

You were being taught to write as part of a transaction that had

Almost nothing to do with real communication.”

You remember this, don’t you? How school writing was required and topics were assigned? How the pointlessness of it all probably made you dislike writing–and even worse, confused you about what good writing is?

And do you remember me telling you that kids needs authentic audiences for their writing? Audiences beyond Mom and Dad?

“Start by learning to recognize what interests you.

Most people have been taught that what they notice doesn’t matter.

So they never learn to notice,

Not even what interests them.

Or they assume that the world has been completely pre-noticed,

Already sifted and sorted and categorized

By everyone else, by people with real authority.

And so they write about pre-authorized subjects in pre-authorized language.”

Our kids know what interests them! Let them write about it. Even if they want to write about Pokemon or My Littlest Pet Shop or the character development of Bruce Banner.

“You were bored from the start and for good reason.

You were repeatedly asked to persuade or demonstrate or argue,

To reiterate or prove or recite or exemplify

To go through the motions of writing.

You were almost never asked to notice or observe, witness or testify.

You were being taught to manage the evidence gathered from other authorities

Instead of cultivating your own—

To stimulate logic

But not to write so clearly that

What you were writing seemed self-evident.”

When kids write about their interests, the acts of observing, witnessing and testifying are built in. The kids have already observed deeply; they’ve witnessed at a microscopic level. They burn to testify to what they know. They have a lot to say.

“You were taught in school to repose on the authority of the evidence you gathered,

The resplendent figures you quoted.

You remember those papers filled with great lumps of quotation.

Your sentences piloted around them like a ship among icebergs.But what if you were to muster your own authority?

…What if the reader believed, somehow, in you?

Listened for your voice, not the voices of others?

Watched for your perceptions?

What if the reader felt your authority

And thought about quoting you?”

The icebergs give me goosebumps. Not because of the apt arctic simile, but because I remember my school papers and those icebergs of quotes. The real goosebumps come with that last line, though, with that small, italicized you. Don’t you want this for your kids? Here’s the thing: kids who read and are read to, kids who are left to write about what matters to them, and aren’t taught too much about how to do it, will naturally write vivid, quotable lines. It’s what kids do, when they haven’t been taught to do otherwise.

(And I see the irony, too, in pasting so many of Klinkenborg’s quotes here, icebergs in their own right, with my little sentences sailing in between. I’ve already written about the stuff of this post, though, many times. I’m simply trying to let Klinkenborg convince you, in case you don’t believe me.)

“What we’re working on precedes genre.

For our purposes, genre is meaningless.

It’s a method of shelving books and awarding prizes.Every form of writing turns the world into language.

Fiction and nonfiction resemble each other far more closely than they do any actual event.”

Which is why I have told you not to get hung up on assigning various genres and writing formats to your kids. Engaged writing is what matters. Let them write in the genres they like. Kids who have learned to manipulate words for their own purposes will be able to handle any format thrown at them.

“And yet good prose often sounds spoken

As if the writer—or the reader reading aloud—were saying the sentences.

(This isn’t the same as sounding colloquial.)

But the arc of education—and the arc of emulation—are usually

Away from spokenness and toward the unspeakable,

Toward longer, more convoluted sentences

Using more elaborate syntax and more jargon-like diction.”

How do you help your kids write good prose that sounds spoken? They can do this quite naturally, from a young age, if you take dictation from them. Dictation will help them develop clear, lively writing voices. It may keep them from muddling up their writing with prose that attempts to sound smart while saying nothing of substance. Curse of the traditionally schooled writer.

“In school you learned to write as if the reader

Were in constant danger of getting lost,

A problem you were taught to solve not by writing clearly

But by shackling your sentences and paragraphs together…

Why were you taught to dwell on transitions?

It was assumed that you can’t write clearly

And that even if you could write clearly,

The reader needs a handrail through your prose.”

This is but a single example of the dangers of over-teaching writing. Klinkenborg delves into many ill-advised rules and pointless techniques that have been piled upon students in the guise of writing instruction. Techniques which adult writing students must shake off in order to learn to write well.

If you are a parent trying to help your kids become writers, you would do well to teach less. Your teaching is likely to be a replay of the bad writing instruction you received. You may ask, if you don’t teach, what can you do? You might help your kids recognize when their writing is successful:

“If you write a good sentence, how will you know it’s good?

You may know it’s good, feel certain about it.

But you’re likelier to sense an inward indifference,

A subtle feeling telling you this sentence isn’t the same as the others.

Even beginning writers notice this.

Learning that feeling is important.

It’s a guide and an incentive to making more good sentences.”

I’m convinced that one of the most useful acts we can do for novice writers is to help them recognize what they’re doing well. I devote a good chunk of my upcoming book to the benefits of positive feedback for young writer’s workshop participants. (The book is coming! November!) I argue that positive feedback can be more instructive than criticism. As Klinkenborg points out in that last line: It’s a guide and an incentive to making more good sentences.

These are just a few of the short, wise sentences that Klinkenborg shares in his book. I’m not sure it’s kosher that I’ve copied so many of them here. I hope I’ve made you hungry for more, and that you will consider buying the book. (And you won’t want a library copy if you are inclined to underlining or highlighting. I have never highlighted a book so. At least not since college.)

The book would be a wise purchase if you are an adult who wants to write better.

It might be an even wiser purchase if you are a parent who aims to raise writers. It may help you separate the useless in your writing experience from the valuable. It may remind you how much reading teaches writing. It may help you trust your child’s fine instincts about writing. It may have you teaching less, and fostering intuition more. Criticizing less, and helping kids recognize their strengths more. It may help you see the value in allowing kids to write about what matters to them, for people who matter to them. It may help you see the writers already existing within your children.

It might help you start your kids on the right path, so they don’t grow up and need to begin again, teaching themselves how to write.

(Edited to add: I forgot to mention that the second part of the book contains exercises that may be particularly useful to a parent who aims to raise writers. Klinkenborg includes passages from some wonderful literature, and poses useful questions for the reader to consider, beyond the unhelpful do you like it? This section could give you ideas for discussing literature with your kids. Also, Klinkenborg shares lines from college students’ writing that seem just fine on the surface, but have underlying errors that confuse the reader. He explains what those errors are. Very instructive for anyone who instructs others on writing.)

Thank you for sharing this post. I’ve been worried that I haven’t been teaching enough writing to my son (one of the reasons we pulled him from public school was they weren’t doing enough), but based on this post, we’re still doing good things – lots of writing and playing with words. I have been doing dictation with him (he’s 9), which I’ve seen removes the stress of physically writing or typing from the joy of creating. I also ordered a book called Rip the Page which is all about playing with words, which we’ve both been enjoying. Perhaps I need to pick up this book as well!

It does sound like you’re doing so many good things, Natalie. I am a huge fan of dictation (which you may know if you’ve read my dictation series in the sidebar.) And I love Rip the Page! It’s one of my favorite writing resources. It sounds like you’re doing the activities together, perhaps? I know of other families who use the book that way, and it seems like a fantastic, fun idea.

I’d love to hear how things go with your son’s writing over time. Thanks for responding!

I have read your dictation series, and taken it to heart. It really does seem to help the writing process in my son. We are using Rip the Page as a family – even my six-year old daughter gets involved when she can use dictation (see – there it is again 🙂 ). I am amazed at the creative phrases that come out of his mouth – much more sophisticated than I would have expected based on his age. I just reviewed Rip the Page over at my blog, and provided a few samples of the writing that we’ve been doing. He’s come up with things like: “I can write with the infinite particles that make up the universe” and “I can write with the traces of smoke from the fire of life.”

Loved the review, Natalie. Your kids are most certainly writers. Keep doing what you’re doing!

Ooooo—Rip the Page looks like the kind of writing I want to do, too! I veer toward Left-Brained strictness/order but there’s a Right-Brained side simmering just beneath. This book would peel back the layer to let her loose…

Get the book and try out some of the exercises with your kids, Jennifer! Might be as good for your kids as for you!

Always interest in a good book on writing–this one sounds like a winner! Thanks for the recommendation!

If you like the excerpts I’ve shared here, Wendy, then I think you’d like the book. It’s a good one!

wonderful recommendation – i think this needs to be a part of our home library, for me AND for my budding writer, who says she’s not interested in writing for contests or in response to prompts. she says she *can* write with that aim in mind, but would much rather write when she feels that compulsion, that need to get the thoughts out of her mind and down on paper.

from the excerpts you posted, this book could serve as a kind of therapy for me, recovering from years and years of an educational system and subsequent career choices that relentlessly and consistently pounded into me that there was the *right* way to write, and i was not doing it. that there was something wrong with me because i couldn’t (or wouldn’t?) take a formula and stick in my own words and make it compelling for a reader, who was probably only looking at it in order to give me a grade anyway. and it only got worse as i went from high school to college and then multiple graduate degrees.

the writing i most enjoy reading is raw and direct and from the heart, as if i were having an intimate conversation with the author face-to-face. my daughter shuns anything that reads as *textbooky* and standoffish and formal; she prefers a storytelling style that is engaging and inclusive.

looking forward to your upcoming book, too, patricia!

now i think i’ll go read out loud to my kids, though they can do it alone. it’s something we all enjoy, and it’s good for us, too.

Dawn, I do think the book could serve as a sort of therapy for you. 🙂 I know that you’ve written before about how your academic writing experiences undermined your confidence and enjoyment of writing. Klinkenborg directly addresses that notion of there being one *right* way to write–which is so wrong-headed!

I think the book would speak to you.

It seems like your daughter has some very good instincts about writing. Glad that you recognize them!

Lying in bed & reading Percy Jackson w/my son (we take turns) makes a good writer.

Walking through a cross country trail and talking about what fall glories look like makes a writer.

Listening to my daughter read Little House in the Big Woods (which I never tire of reading) makes a good writer.

And here I had twinges of not “teaching” writing yesterday.

Yep. You got it, Jennifer!

Not that I needed Klinkenborg to convince me as I’m already sold on the ideas you’ve presented here and use them regularly but reading this, I’m pumping my fist into the air and nodding in excitement to have it put so eloquently. Even better, knowing that the book is already winging it’s way to my house so I can have at my copy with a highlighter! I have a feeling this book will be one I devour rather than read 😉

Klinkenborg is nothing if not eloquent. You in particular, Amanda, will love it, I know. Get that highlighter ready!

Klinkenborg was a speaker at a writing conference I went to many moons ago. I enjoyed his reading so much that I bought his book, which was a collection of columns for the NYTimes. I have heard of this new book of his and thought it sounded good. Thank you for sharing some of it and reinforcing many of my own thoughts on writing/teaching writing. I’ll check out the book!

I’d love to hear Klinkenborg speak sometime, Shelli! I’m intrigued with his choice to write this book in such a unique, prose-poemish style. I’d love to read some of his columns to see how they compare.

Hi Patricia…

I loved loved this. It’s effect on me was to very deliberately stop paraphrasing Gemma’s reading sessions. She chooses loooong stories and is still in the “rush and turn the page” place (she’s 2). After reading this I thought it might be time to help her slow that reaction down a little, and I started asking her questions about the pictures, adding musicality to my reading (thankfully she chose something that had nice flow), and just savoring the experience of having her with me and reading to her. Of course I got so much more out of it than just thinking “I’m creating a good little writer”. Toppled hubris, the lynchpin of my mothering.

Thank you for giving me pause – which gave me a chance to enjoy her in new way.

There’s a thread on Lori’s PBH forum right now about critique, too, in which I shared the link to this post because I felt it was relevant. Hope that’s ok?

Well, we can thank Klinkenborg, because he’s the one reminding us how important reading is in making writers. Sometimes it’s hard to fathom how what you do with a two-year-old has an impact on what comes later.

Sharing is always okay! You may stand out on street corners with photocopies if you’d like!

Wouldn’t Toppled Hubris be a fabulous title for a parenting book or blog? Pretty much sums up what it’s all about. Love that phrase!

After reading your post, I immediately put this book on hold at the library. It arrived a few days ago and I tore through it–what a gem it is! The timing was perfect, as I’m just beginning revisions on my novel (first draft is done!), and I can’t believe how much I *needed* to read it. I love your comments on how it applies to teaching writing to children as well.

Thank you so much for introducing me to such a wonderful resource!

Isn’t it so good, Alanna? I’m glad you liked it as much as I did!

Good luck on your novel. Finishing the first draft is a huge accomplishment!

Way back in the almost-mythical past, when I was training to teach primary school, I had a few weeks’ placement in a multi-age class. I gave each of the (half-dozen or so) year 5 kids a little notebook, with a question from me on the first page. They all said something like, “What do you care about?” And I asked them to write something, and pass it back to me within a couple of days. I responded as an interested adult, I guess, and some of them turned into quite meaningful conversations. Others petered out pretty much straight away. I already knew I hated forced writing topics, I just didn’t know what to do about it.

Now I know. 🙂