Dear fellow wonderer,

A stat for you: After increasing steadily from the 1950s on, American children’s creativity began to decrease, beginning in 1990. Declines have continued, year after year, research tells us, until at least 2021.

Likely, you have questions. According to who? How was this creativity measured? What do you mean by creativity anyway? Are just we talking about kids fingerpainting and writing riddles and making shoebox dioramas?

We’ll get to to this, all of it. But first, please sit with this: since 1990, children’s creativity has been decreasing. It shows no sign of stopping.

Maybe that alarms you as much as it does me. Maybe, like me, you wonder why no one seems to be talking about it.

* * *

My interest in creativity goes back to my psych major days. (Goes back further but let’s save the slightly melodramatic origins of my own creativity story for the book.) The ability to apply psychology research in creative ways led me to teaching, and the promise of encouraging my own kids’ creativity led to homeschooling. The original tagline for my blog, way back in 2008: Where a mother tries to cultivate a sense of creativity and wonder in her kids—and does a whole lot of wondering herself in the process.

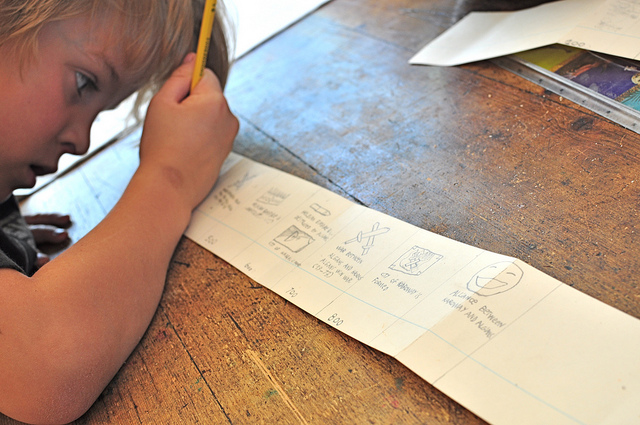

Once upon a time, when my youngest was nine, he wanted to make a timeline and, damn, did I think this was a good idea. I’d always dreamed of being the kind of homeschooling family who had timelines snaking up the stairwell (though this would probably have been my husband’s nightmare.) For days, the kid and I had spread across our family room floor a really cool synchronoptic history chart. It showed events from different cultures at the same time in history, lined up for comparison. (That physical timeline is no longer available, but the website is still active though charmingly dated and endlessly fun for clicking around.) Mr. T loved the little symbols used with some of the historical figures and chronologies–very Pokémonesque. Around that time we’d also been listening to an audiobook history of the world. T’s idea was, get this, to make a timeline based on the cultures we’d been hearing about. I rustled up some old sentence strips from my teaching days, laid them across the kitchen table and felt like Richard Scarry’s Best Homeschooling Mom Ever.

Warning, warning! Traipse through the archives of my blog and you’ll find story after story of my kids knocking sideways my ingrained beliefs about academic learning. That morning seemed so ideal, Mr. T studying that historical chart on the floor, taking it in like a scholar. When he looked at me with big eyes, I must have seen it coming.

“I know what I can do!” he said. “I can make a timeline of my own world!”

* * *

Despite my longstanding interest in creativity, I hadn’t heard of these childhood creativity losses until recently, when, researching for my book, I happened upon a Newsweek cover story from 2010, “The Creativity Crisis.” Written by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman, the article looks at the work of researcher Kyung Hee Kim, who analyzed almost 300,000 creativity tests of American children, dating back to the 1950s, before spotting the 1990 shift.

Kim’s background is inspiring. She grew up in a poor South Korean mountain village near an American military base. In middle school, she won a scholarship from those soldiers that changed her life, allowing her to further her education and eventually earn a PhD. But Kim grew increasingly frustrated by a culture that stifled her curiosity and love of questions. At thirty-three, she fled to America with her children, eventually finding her way to the “Father of Creativity,” a.k.a. Dr. Ellis Paul Torrance, the creator of the Torrance Test of Creativity, with whom she studied.

Torrance’s test involves a variety of verbal and non-verbal tasks, everything from finding unusual uses for tin cans and books, sketching objects featuring circles, suggesting ways for improving a toy, to solving Old Mother Hubbard’s problem of finding no bone in the cupboard.

The Torrance Test of Creativity is well respected, “the gold standard in creativity assessment” according to Bronson and Merryman, its validity underscored by how researchers track test-taking children for years, well into adulthood, with impressive prediction rates. From the Newsweek article: “Those who came up with more good ideas on Torrance’s tasks grew up to be entrepreneurs, inventors, college presidents, authors, doctors, diplomats, and software developers.”

Note here that we’re not just talking about artists. We’ll get to that.

Under Torrance’s tutelage, Kim earned a second PhD and began questioning the long-assumed link between creativity and intelligence, leading her to analyze those nearly 300,000 test results dating back to the 1950s.

Kim shared her results in a 2011 paper in the Creativity Research Journal. Her hypothesis was correct: creativity and intelligence were not directly linked in her analysis. Even more: she recognized what no one had previously seen, the downward trend in children’s creativity.

Since 1990, Kim writes in the paper, “children became less emotionally expressive, less energetic, less talkative and verbally expressive, less humorous, less imaginative, less unconventional, less lively and passionate, less perceptive, less apt to connect seemingly irrelevant things, less synthesizing, and less likely to see things from a different angle.”

!!!!!!!! is what appears in my notebook opposite this sentence, a sentence I’ve copied there word for word, feeling increasingly devastated as I transcribed each adjective.

* * *

That morning with Mr. T, Richard Scarry’s Best Homeschooling Mom Ever faded from the page as quickly as she’d appeared. A timeline of his own world. The world from a grand story he’d been dictating to me is what he meant, I knew. That sounded fun and all, but the history education aspect of his original timeline disappeared along with the ghost of the Best Homeschooling Mom Ever and her apple. I kept my sigh almost inaudible and asked about his plan. If I’d learned nothing else as a homeschooling parent, at least I understood that it’s best to take the direction that captures the kid’s imagination. Good things happen when they’re captivated.

“How do I start?” T asked, a blank sentence strip before him. “Do I start with how the world was created?”

“Why don’t you look the other timeline to see how they started it?”

After initially sketching individual creatures and their evolutions, T decided that his history was plodding along too slowly. Back to the timeline in the living room he went to consult. At the kitchen table he erased and wrote War between the Gnomashins and Afradys. Afradys win war. (year 39-57)

“I’m making a key!” he sang, and drew a set of crossed swords above that entry and in a square at the end of his timeline.

* * *

In “The Creativity Crisis,” Kim’s 2011 paper, she writes that the creativity decline is “steady and persistent,” and “begins in young children, which is especially concerning as it stunts abilities which are supposed to develop over a lifetime.”

Causes for the decline, Kim hypothesizes, include diminishing free, uninterrupted time in childrens’ lives. “Hurried lifestyles and a focus on academics and enrichment activities have led to over-scheduling structured activities and academic-focused programs at the expense of playtime.” (You know I’m on Team Kim here.)

She also notes how increased time with electronic entertainment has led to less free play.

In 2016, as children’s creativity scores continued to decrease, Kim published a book, The Creativity Challenge, delving further. She writes, “my research points to a gradual society-wide shift away from the values that were the foundation of American creativity.”

Sigh.

Factors leading to this shift, Kim believes, include financial insecurity, leading parents to push their children toward more structured education, aimed at “secure careers.” And, as students from other nations began outperforming American children on international assessments, politicians and education leaders (and business leaders, I’d add) decided a revamp of the public education was in order. This unleashed the No Child Behind Act of 2001, and later federal iterations, all with a focus on standardized curricula and testing.

Standardized curricula and testing.

More standardized curricula.

More testing.

Most parents seem aware that testing has become a huge part of the public school experience. I’m not sure that all realize how much the curriculum itself has changed. To earn funding, public schools focus on tested subjects–math, reading, language arts–and have reduced time spent on other subjects. Not only the arts, always the first to get slashed, but also science, social studies, PE, foreign languages.

And recess.

And it’s not just the subject matter, but the way material is taught, as I discussed in my first newsletter. Like I said, when I taught elementary school in the early ’90s, the prevailing educational pedagogy was a problem-solving, critical thinking approach–in other words, a creative thinking approach. That’s been replaced by a focus on teaching kids specific “skills” they need to succeed on specific tests.

* * *

As I watched Mr. T run back and forth between the timeline in the living room and his own timeline, I began to see that I might have been wrong about this activity not being educational. T wasn’t simply copying an existing timeline–which is surely what he would have essentially done if he’d made a timeline based on actual events. Rather, he was using a professional model to inform his own notions. After wars, he created cities; after cities he made empires, then more wars, then alliances. The Karoway-Algian Alliance, for example. And he was applying not only what he’d learned from the professional timeline, but what he’d picked up from the world history audiobook we’d been listening to.

The entire time he worked: utterly focused. As he was the next morning, when he added to his timeline while eating his toast.

Again and again, when I allowed my kids to indulge in creative projects, even creative projects that seemed merely frivolous, they’d astound me with how they thought, what they learned. I’ll share some humbling examples in a few weeks, in our next Wonder-Room.

Big lessons I learned as a mother: pay attention to where my kids aimed their attention. And listen. In her 2011 paper, Kim writes, “lost in the rush to provide ever more stimuli and opportunities to children is time for adults to listen to their children…A child needs meaningful interactions and collaborations to be creative.”

* * *

“Art bias” is what one researcher in the Newsweek article calls the belief that creative thinking is just for artistic people. Consider that list of professions for adults who received high scores on the Torrance Test as children: entrepreneurs, inventors, college presidents, authors, doctors, diplomats, and software developers.

Creative thinking, as Bronson and Merryman point out, “requires constant shifting, blender pulses of both divergent thinking and convergent thinking, to combine new information with old and forgotten ideas.”

Kinda like making a timeline of your own world while consulting a timeline grounded in history.

There’s a fantastic story in the Newsweek piece about a curriculum Ohio middle school teachers developed to help their fifth graders employ this kind of thinking. Read about the project and the kids’ engagement with it. Then read about their resulting standardized test scores (and don’t make assumptions about this being a privileged population.)

* * *

The timing here sucks. We’ve been stealing creativity from kids just when they might need it most.

Young people are struggling with their mental health. We adults seem hell-bent on blaming this on phones and social media, but we might note that, as Bronson and Merryman point out, creativity is associated with positive mental health. “Creative thinkers are engaged, motivated, and open to the world.”

On the other hand, as a researcher suggests in the article, an inability to imagine alternate options “leads to despair.” Despair: an absence of hope. Despair: a feeling many young people are telling us they can’t escape.

One of most important aspects of creative thinking: it allows people to imagine different possibilities. And, geez, do we need to help people, young and old, imagine different possibilities right now. For themselves. For this world we seem bent on imploding.

This, to me, should rally our protest: Since 1990, children became less emotionally expressive, less energetic, less talkative and verbally expressive, less humorous, less imaginative, less unconventional, less lively and passionate, less perceptive, less apt to connect seemingly irrelevant things, less synthesizing, and less likely to see things from a different angle.

We can’t keep doing this to kids. Kim has noted continued creativity declines, as recently at 2021. It’s time to convene, to fight, to figure out how we can do better. In our next Wonder-Room letter, I’ll share some links. Meanwhile, let’s talk.

What can we do? How does this research hit you? How can we bring more creative thinking into kids’ lives? And what can we do about creative thinking in schools? There’s a lot of work to do here.

Let’s go.

Truly,

Patricia