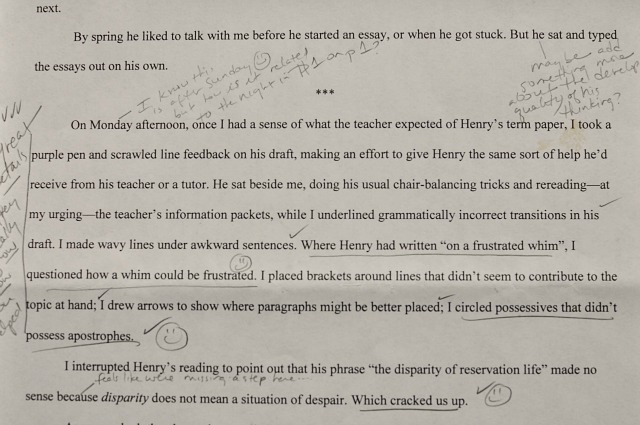

Feedback on one of my drafts from a writing friend. Note all of the smiley faces and “I like this” checks. I learned that I’d done something right in this paragraph.

All I ever meant to do was write a simple post on how a parent might offer writing feedback to their kids.

I’d written this post on the (unfortunately now defunct) Spilling Ink blog about how to offer feedback to a fellow writer, and I figured I’d adapt it for parents.

But how could I write about becoming a writing mentor without exploring the difference between a teacher and a mentor? And if I wanted to convince you that mentorship works, I had to write about how much kids learn without being taught. Then it seemed that we should examine what mentorship might look like. And if we were talking about writing mentorship, we couldn’t ignore spelling and grammar, because those are often the elephants in the room that get in the way of mentorship for parents. And of course we needed to address finding meaningful writing for kids, because if kids don’t care about writing, there isn’t much to mentor in the first place.

So here we are, somehow, in part seven of a series that was meant to be a single post. This is like the Star Wars of blog series. What was just meant to be a single entity keeps going and going–until eventually even Disney gets involved.

Good news, though! I think I can tie things up in two posts (with no Disney princess tie-ins, even.)

So, next post, the promised tips for offering feedback. And today: some thoughts on why positive feedback is so important.

As parents, we know the value of encouraging our children. Admiring their drawings, thanking them when they remember to put their dishes in the dishwasher. When it comes to our kids’ writing, though, many of us find ourselves lapsing into the role of teacher, rather than encouraging parent. (Which is where I was going with that first teacher versus mentor post.) We may look at our kid’s writing and seize up at the sloppy handwriting, the spelling errors, the missing periods and capital letters. Our concerns about our child’s writing development may impair our ability to see much positive in their writing at all. How can we offer positive feedback when there is so much that needs to be fixed? (I know how this goes. I’ve been there too.)

I hope to convince you that turning your attention from what needs to be fixed, and focusing on the positive may be more powerful than you realize. I don’t mean this in a new-agey, touchy-feely, praise-your-kids-about-everything way. Simply put, I’ve discovered this: if you offer almost exclusively positive feedback on your child’s writing, your child will likely develop as a writer.

If you’ve read my book on writer’s workshops, you know my thoughts on positive feedback. I want to share a story, adapted from the book—with a few insertions to remind you that what works in a writer’s workshop works for parents and their own kids as well.

Years ago, I took a writing class at my local adult school, taught by a woman named Charlotte Cook. I think I paid sixty dollars for a ten-week course, and it may have been the best sixty dollars I’ve ever spent, because Charlotte was one of the finest writing teachers I’ve ever watched in action. Over the years I’ve taken a collection of much more expensive writing courses through university extension and the like, but no instructor ever pulled off the magic that Charlotte did in a high school Civics classroom each Wednesday night. She had a gift for pinpointing the strengths in any writer’s work, no matter how unpracticed those writers were. The nutty psychotherapist whose mysteries strayed aimlessly learned that she had an ear for dialogue; the quiet young mother who timidly shared her personal essays discovered that her lines had the lilt of poetry. Charlotte helped me understand for the first time that I had a knack for choosing details, which has kept me searching for the right ones ever since. Sometimes I’d listen to a classmate’s contribution for the week and I’d think what will Charlotte possibly find good in that? And then Charlotte would find something. She didn’t dwell on what our worked lacked, the way teachers in my other courses seemed to do; instead, she kept digging into the garage sale heaps of our drafts and drawing out treasures, with a big grin on her face. Sometimes the treasures were small, no bigger than napkin rings, but they were enough to keep us writing, and polishing, until we slowly began to recognize, on our own, where our words had worth.

As a facilitator of writer’s workshops—and as a parent—I’ve always tried to emulate Charlotte’s treasure-digging.

Positive feedback gives a writer more than just confidence; it gives us a sense of how to proceed. If we know what we’re doing well, we’re likely to keep doing it. Our strengths as writers are not always obvious from where we sit behind the pen or the keyboard, but having them proclaimed and explained in a workshop setting—or by a parent—begins begins to establish and solidify them. They become like handholds on a climbing wall: once we have a solid footing in one area, we can creep to that next spot, just a little farther up, and take a new risk in our writing. Positive feedback offers a map of where to begin, and suggestions for where to go. Too much critical feedback, on the other hand, simply gives a map of spots to avoid, labeled with skulls and crossbones. It’s hard to get anywhere when you’re just trying to keep out of trouble.

Many of us make it to adulthood with no sense of our own strengths as writers—we may not recognize that we write with clarity, or sensitivity, or that we’ve inherited our crazy cowboy grandfathers’ knack for spinning a gripping tale. Yet in a workshop environment—or with the feedback of a caring parent—kids gain a sense of their strengths from the start.

Why positive feedback is more valuable than parents may realize:

- Positive feedback helps kids understand what they’re doing well. Overly critical feedback simply teaches kids what not to do; it doesn’t teach them how to proceed.

- Kids are more likely to move forward and try new things if they feel secure in what they can do already. On the other hand, if their work seems faulty and full of errors, the idea of trying again can be overwhelming.

- If kids feel that a parent—or another reader—is a supportive reader, they will be more likely to go to that person for future writing help. If a reader is overly critical, kids may be hesitant to share their work with that person.

- Kids who receive positive feedback on what they’ve attempted learn to trust their powerful writing instincts. Kids who receive too much critical feedback are less likely to trust their intuitions, which makes it hard for them to develop unique, powerful writing voices.

- Positive feedback tends to focus on what already exists in the writing—which is what the writer is likely to want to focus on. Critical feedback tends to focus on what the reader considers to be wrong or lacking in the writing. Often, critical feedback is centered on the reader’s preferences and biases, rather than what the writer wants to accomplish.

Kids who feel good about their writing are likely to want to continue writing, and this internal motivation is likely to be the most powerful factor in their development as writers. In his book, Several Short Sentences About Writing, which you know I love, August Klinkenborg writes,

“If you write a good sentence, how will you know it’s good?

You may know it’s good, feel certain about it.

But you’re likelier to sense an inward indifference,

A subtle feeling telling you this sentence isn’t the same as the others.

Even beginning writers notice this.

Learning that feeling is important.

It’s a guide and an incentive to making more good sentences.”

Kids need to learn that feeling of recognizing what they’re doing well on their own. Our positive feedback can get them started. Their recognition of their own successes will be that “guide and…incentive to making more good sentences.” Kids who feel discouraged and overwhelmed with writing, on the other hand, are not likely to want to write. They won’t have the power of internal motivation to keep them writing. The drive to make more good sentences is the simple requirement for improving as a writer.

We’ll talk more about how to give positive feedback in the last installment of the series. It can be harder than it sounds to stick with the positive, I know. Basically, note what your kids are doing well in their writing and tell them why it appeals to you. Be like Charlotte and emerge from reading their work with a big grin and some thoughts about what you admire. (Even if the treasures are tiny as napkin rings.)

Which is not to say that kids don’t ever need constructive feedback. More on that next time too. But when in doubt, err on the positive side. Keep guiding your kids to the good sentences they’ve already written.

You can read all posts in this series here.

Great post, absolutely spot on! I had two years of grad school classes in the teaching of writing, and one finding from current research that was impressed upon us as we headed into the classroom to teach freshman writing was that kids usually only took in two criticisms/suggestions before switching off and simply concentrating on their grade: TWO. Compare this with the typical paper covered in suggestions for rephrasing, questions, grammatical corrections, etc. Then compare with the typical grad student corrections, which could go on for two typed PAGES. The poor students! And poor us, laboring for hours over helpful suggestions (we thought) which would never be taken in, much less carried out. We never once had anyone talk to us about the power of positive comments.

Here’s a slightly different slant on the same general topic: I remember years ago reading a passage in one of Lucy Calkins’s writing instruction books, which chronicled a classroom writers’ workshop at the elementary level. A young girl had written a touching paragraph about her sense of isolation at school. The kids began giving the types of comments they had been trained to give, which they knew by now the teacher wanted: “You need more detail here,” or “I’d like to know what so-and-s0 looks like,” or even something along the lines of adding more verbs or adjectives. The girl sat silently while the comments went around the circle. Finally one child walked up to the girl in her chair and said, “I’ll be your friend.”

I think sometimes we become so caught up in issues of correctness, clarity, style, etc. that we completely forget that writing is always an act of communication, and that above all, writers who share their work want to be heard. Some of the best experiences of writing with my daughter have come when I’ve ignored the spelling and grammar, ignored the phrasing, even neglected to point out positive aspects of her wording or details that leaped out at me, and said, “That is so interesting! I didn’t know you thought that. How did it occur to you? What else have you been thinking about it?” Or on occasion, instead of saying that I wanted to read more or know more, I’d say, “You make me want to write about something similar myself!” or “You’ve given me the greatest idea for my next piece.” And then I write it.

There is so much good insight here, Karen. Your point about students only taking in two suggestions is interesting. Personal experience has taught me that it’s best to keep constructive feedback narrowed to a few key points–good to know there’s research to back that up!

The Calkins story is heartbreaking. I offer a similar one, shared by a friend, in my book. Only in that instance none of the other kids recognized how much they were tearing the writer down. The Calkins story is especially poignant because the kids were doing what they’d been “trained” to do. This is why I spend so much time helping kids learn to give positive feedback in my workshops. Seems like it’s human nature to recognize how others might improve; it can be more challenging to see the positive in others and their work. But kids–and adults–can be “trained” to see the positive as well.

Your third paragraph is so wise, and I appreciate being reminded of this. Yes! We write to connect, and acknowledging that connection and our interest is probably the best we can offer a fellow writer, of any age. Much more important than any specific feedback. Your examples of how you’ve responded to your daughter are excellent models of how parents might respond to their kids’ work in a meaningful way. Thank you.

I love your articles about writing! I extrapolate from them, to guide me in my journey in parenting. I just forwarded this to my husband as well, as it offers so much wisdom in other areas of our children’s lives as well. Thanks so much, from a non-writer, but voracious reader, who enjoys your blog immensely!

You’re right, Lisa. These tips can really be applied to many aspects of parenting. Focusing on what kids are doing well makes so much more sense than focusing on what they’re doing “wrong.”

Some of my most treasured compliments are when readers tell me they’ve shared something here with a spouse or friend. Thanks for the support!

hopefully subscribing…

…and hopefully you get an automatic notification to this response! You’ll need to do this every time you leave a comment, but I hope you agree that it’s pretty simple. (If you decide that you don’t want a notification to *all* comments on this post, Lisa, you can use the link in the email notification at any time to change your subscription to replies to your comments only.)

I can attest to your stick-to-it nature of providing positive feedback for writers in your workshops.

You emulated “Charlotte’s treasure-digging ” in every writer’s workshop I’ve ever sat in of yours.

In fact, I was always impressed by how easy it seemed for you to note specific aspects of a kid’s piece.

Because you modeled that so well, I made a point of doing the same thing in my writing group.

It felt good to be positive with them, and by that I mean sharing meaningful examples of their writing style–not just saying “good job” and giving them a thumbs-up.

Maybe you are a cheerleader at heart. (I happen to know that you still fit into your high school uniform;-))

Hey Kristin! I didn’t manage to respond to this before our trip–and then life got busy!

Thank you for the kind words about the feedback I’ve offered to kids. I think you get better at it the more you do it. Once you realize that positive feedback can actually be helpful, and that it isn’t just something you do to be polite, you understand that it’s worth the effort. And then everyone in the group gets better at giving it. It’s neat.

I am totally a cheerleader at heart. But I only fit into my uniform if I leave the skirt unzipped.

I largely agree with your argument here about the importance of offering positive feedback on writing projects. I taught college writing for years and undergrad and graduate level lit classes as well and read (and commented on) more papers than I can count. Now that I am teaching my own kids, I know where I do NOT want them to end up more than I know what I want them to learn or do right now. The path is a tricky one to maneuver, and I am trying to do it from from a place of respect for their interests and abilities seasoned with a bit of guidance and advice now and then. When reading my son’s writing, I give a lot of concrete, well-deserved praise (for effort, for doing something that he has struggled with in the past, for sticking with a project he wasn’t sure about, etc.), but I also make suggestions about possibly looking carefully at where he might correct a few capital letters or ways he might think about how he could do one thing or another in his next project (which allows me to validate his current work while still helping work toward improvement). I think you can give suggestions and offer constructive criticism if it is done respectfully. Part of my job is to help him become better and I don’t think I can do that if I don’t at least point out a few things he might work to improve.

Hi Erica,

How lucky for your son that he has a college writing instructor as a homeschooling parent!

You write, “Now that I am teaching my own kids, I know where I do NOT want them to end up more than I know what I want them to learn or do right now. The path is a tricky one to maneuver, and I am trying to do it from from a place of respect for their interests and abilities seasoned with a bit of guidance and advice now and then.”

Speaking as a fellow former teacher, I understand why you find this path tricky. I think it can be hard to let go of what we think our kids should know, and let our kids guide us towards what they want to know. Focusing on the positive in their work and play is very helpful with this. It allows us to pay attention to what they’re doing, and what they’re doing well, rather than keeping us caught up in our own preconceptions.

I agree that you can give suggestions and constructive advice if you offer it respectfully. As I hinted at towards the end of this post, that’s what I’ll be writing about in my final installment in the series. It’s a complicated topic. Our ultimate goal, I think, should be becoming a reader who our child respects, who they want to bring their work to for advice. Sometimes getting there means we need to stick with the positive and swallow the advice more than we might realize.

Hi Patricia,

Boy is this timely. Although my son is taking some of his classes in our local co-op, I am doing reading/writing with him. And I was surprised at myself the other day reading one of his essays and offering completely non-helpful “constructive” (Arrghhhh) criticism.

I didn’t feel it was his best work(He is a wonderful writer) but I knew I was not leading him toward something meaningful in my comments,

And me, a writing project, process- oriented person! Geez.

So thanks for these reminders of what writing mentoring can and should be.

Best,

Emmie

Emmie, it can be so hard not to rein in the constructive comments, can’t it? Especially when you are a parent who wants your child to grow as a writer. I think, usually, our intentions are good. We want to help.

“…I knew I was not leading him toward something meaningful in my comments”. This is a lovely way to state what we really ought to aim for: leading our young writers to something meaningful. I’ll be writing more about that in a follow-up post. Meanwhile, thanks for reminding us how easy it is to slip away from our intentions, even if we know better. One thing about sticking with mostly positive feedback: it’s hard to do harm!